|

| Josephine Walcott to Linda de Force Gordon, November 3, 1878 (Bancroft Library, University of California-Berkeley) |

Both women were spiritualists

as well as suffragists. A trance medium with superb oratorical abilities, Linda

often represented the suffrage movement in the political sphere. Correspondence

between the two women shows their

collaboration.

“I lectured successfully at

San Jose and found many liberal pleasant friends,” Josephine reported to Linda in

1878. “It is only among liberal people that woman can find sympathy, or

audience to give utterance to her thought.” But further on, Josephine

confided: “I begin to feel that there is nothing quite worth doing. Why should

we pour forth the rich largess of our thought upon deaf ears?”

She persevered, however. In

1880, the California State Legislature received “A petition from Mrs. Josephine Walcott

and one hundred and eighteen others, asking for legislation such as will permit

women to vote on all school questions.”

|

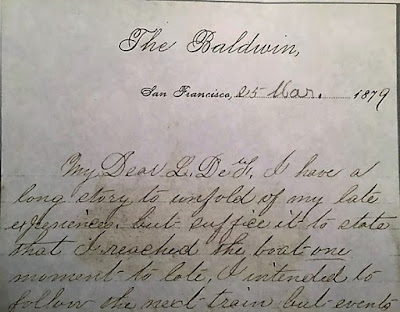

| Josephine Walcott wrote to Linda de Force Gordon from San Francisco's luxurious Baldwin Hotel, 1879 |

She must have been very proud

that her daughters, Mabel and Maude, matriculated at Berkeley the following

year. Both became teachers. Maude married a professor at San Jose State College

and Mabel married William Adam Beatty, son of a policeman, who became a lawyer

in San Francisco. Tragically, Maude and Mabel died young. But Mabel and William

had a son, Willard (see earlier post), who grew up to be a brilliant

progressive educator.

Josephine made an appearance with

baby Willard in a dissertation written by the first female recipient of a PhD

at Berkeley, Milicent Washburn Shinn. Considered a pioneer in developmental

psychology, Milicent asked several young mothers – all Berkeley alumnae – to record

information about their children’s first few years. Her thesis, Notes on the Development of a Child,

includes Mabel’s descriptions of Willard.

Here, I have to interrupt the

story to say that it is extraordinary if not unheard-of to have a detailed

account of a baby, whose life’s work would involve the study of child

development, learning how to walk in 1892.

Charmingly, Mabel reported:

On

the same day on which he first took his hand thus off a chair to walk alone, he

started to walk from his grandmother to me, but when he had gone half way, and

I held out my arms to receive him, he suddenly whirled about and walked back to

his grandmother, evidently pleased that he had played a joke on me.

Josephine surely enjoyed the joke.

After Willard was orphaned in

1901, he became the ward of his uncle Earle. Josephine shared their apartment. She

died in 1906 a few months after the San Francisco Earthquake and five years

before California voted for a proposition granting women the right to vote in

state elections. From a conversation with one of Willard’s granddaughters,

I know that she read her poems to him.

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2015/11/onward-josephine-walcott.html

See also 2015 posts: November 4 + 11 + 29 + December 2; January 12 + 16, 2016.

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2015/11/onward-josephine-walcott.html

See also 2015 posts: November 4 + 11 + 29 + December 2; January 12 + 16, 2016.

No comments:

Post a Comment