|

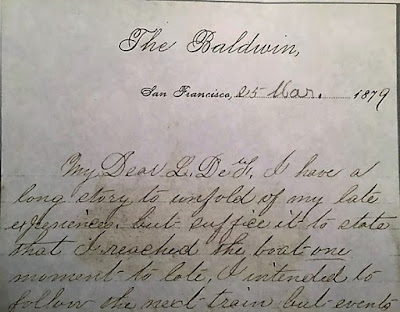

| Josephine Walcott, 1860s |

Both native New Englanders,

they might have met in New Hampshire or Vermont. But John Walcott went out to Magnolia,

Illinois, in 1848 to build houses and a full ten years passed before Josephine Butterfield joined

him and they married.

John enlisted in the 77th

Illinois Regiment and fought for the Union in Tennessee and Mississippi.

Josephine made her way to Chicago to sit for a photograph. Three children were

born during the war years: Earle, Mabel, and Maude.

The children were smart but

Earle turned out to be sickly, so his mother taught him at home. The family

moved to Santa Barbara in 1868, hoping the climate would improve Earle’s

health. A precocious child, he founded and edited the Santa Barbara Weekly Tribune which he published for a few years.

Josephine began to write poetry.

In 1871, a new magazine

called Overland Monthly published her

poem, “Almost.” Encouraged, she wrote more and also published under the name

Cordelia Havens. Several anthologies included her work and critics considered

her a California poetess. A review of her collection, World of Song, cited “clear thought, delicate imagination, good

command of emotional sentiment and a felicitous Tersifloation.”

Tersifloation seems to relate

to phrasing but that’s all I can figure out. A beautiful word, though!

It’s clear that Josephine

pushed her children toward higher education. They enrolled at Santa Barbara

College to prepare for the University of California, Berkeley, from which all

three would graduate. Around that time, Josephine may have had an affair with

William Hollister, owner of a grocery where John Walcott worked as a manager. Hollister

or someone else may have been the father of Marion Queenie, Josephine’s fourth

child who came along in 1882 in San Francisco.

Several years after Queenie’s

birth, John and Josephine filed for divorce but the relationship must have been

very bitter because the court assigned a judge to referee. By then, she and her

husband occupied entirely different worlds.

Josephine fit perfectly into

her time or perhaps the time suited her especially well. How fortuitous that she

arrived in California just as it came into its own art, literature, and politics:

the emergence of a distinctive California ethos. For she was a seeker and it

came naturally to embrace new ideas.

As

an advocate of woman’s suffrage, Josephine wanted to shake off male domination.

And, like many suffragists,

Josephine was a late Victorian spiritualist. The two may seem incongruous. Yet

one of the major ways to escape patriarchy was to step away from conventional

religion. Historians have long explored how women spiritualists, while

communicating with the dead, developed a commitment to social justice including

the 19th century women’s rights movement. It is thought that public

performance boosted their confidence, honed their speaking skills, and exposed

them to issues involving women and children.

In

1874, Josephine co-founded the Freethought Committee of California. Freethought

went hand in hand with spiritualism; its appeal to logic and reason excluded

religious dogma. The same year, Josephine helped organize the Santa Barbara

Spiritualist Association and became its vice president, bringing famous mediums

to speak while the group was denounced for promoting fornication, suicide,

desertion, adultery, divorce, dementia, prostitution, abortion, and insanity.

I

guess it hit a nerve.

Josephine delivered a

lecture, “The Truth Shall Make You Free,” before the Santa Barbara Spiritualist

Association in 1876. An observer commented:

Of Mrs. Walcott, it was said

that her enunciation was clear and pleasant, though a little too rapid for slow

thinkers, for her grand ideas were clothed in so few words, and followed so

rapidly, like booming waves, one after another, upon a storm-beaten shore, that

there were some who could not gather, arrange, and enjoy the beautiful pearls

as they fell from her lips.

Even at this distance, the

lecture holds up. Citing Galileo, Luther, Franklin, Morse, Darwin, and Huxley,

Josephine championed empiricism and declared: “Women are but dimly conscious of

their power, so circumscribed are their limits. . . Woman must be free,

independent, self-reliant and individualized.”

See also: November 4 + 11 + December 2, 2015 posts; January 12 + 16 posts.

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2015/11/enter-josephine-walcott.html