|

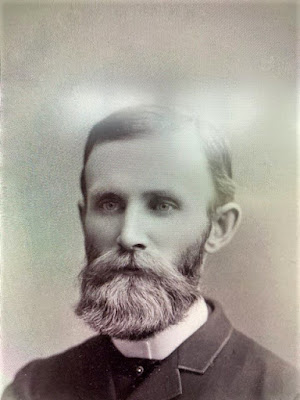

| Frank Sargent Hoffman Professor of Moral and Mental Philosophy, Union College, N.Y. |

Consider the situation of Frank Sargent Hoffman, casting about for work after a railroad job fell through.

Born on a ranch in Wisconsin in 1852, Frank came from a long line of farmers, a

profession he did not want.

He was about 17 years old, with his heart set on becoming a brakeman and rising to the position of conductor. But the distant relative who promised to use his influence changed his mind.

Now here was Frank in the

summer of 1870, traveling along the west bank of the Mississippi River, Dubuque

to St. Louis and back again, hoping to make some money. Frank wasn’t selling cloth,

coffee, tea, boots or dried figs.

|

| Mississippi River where it passes Iowa and Missouri |

No, he peddled just one item: a map that depicted the Franco-Prussian War, created by a friend in Chicago. Frank had dozens of copies in his knapsack, each available for 25 cents to the people of Davenport, Muscatine, Burlington, Keokuk, and so forth.

The maps were popular and Frank often telegraphed his friend in Chicago asking for more to be sent to the express office closest to wherever he happened to be along the river.

|

| Stylized map of the Franco-Prussian War, 1870 (not the one Frank sold) |

Better to be navigating those towns in the summer heat than be caught in the Siege of Metz, which would begin that same August and end in October with Alsace-Lorraine in the grip of the German Empire.

At the close of summer, Frank retreated to Galesburg, Illinois, where he lived with his father and mother and two sisters. After leaving Wisconsin, the family had eventually landed in Galesburg, where they continued to farm.

Galesburg has a few claims to fame. The poet and Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg was born and grew up there. It is also the home of Knox College, founded in 1837 by a group of Protestants and Congregationalists. In the fall of 1870 Frank entered Knox, where he studied for two years before transferring to Amherst College.

Subsequently, Frank

graduated from Amherst, earned a Master of Divinity and a PhD at Yale, studied

in Germany with the philosophers Zeller and Fischer, and became a Professor of

Mental and Moral Philosophy at Union College in Schenectady, New York.

|

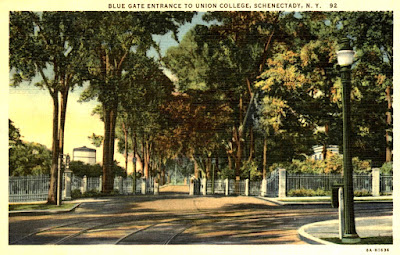

| Union College entrance, early twentieth century |

In 1885, when Frank

arrived at Union College, the school was at its nadir. The student body and

faculty had shrunk, and those who remained lacked morale. An interim president,

Judson S. Landon, was surely more preoccupied with his position as a justice of the

New York Supreme Court.

The Union College website refers to “17 years of unrest and stagnation,” which would constitute a devastating setback for any institution. The story is buried in the college's archives.

Frank Hoffman didn’t save the day but a new president, Harrison Edwin Webster, is said to have improved the mood and tripled enrollment. However, Webster and the presidents who followed him did not like “Hoffy.” Frank’s popularity with students—especially Phi Gamma Delta—may have worked against him. Efforts to ease him out started in 1889 but he managed to hang in until 1917. During those years he published four very dry books: The Sphere of the State (1894), The Sphere of Science (1898), Psychology and Common Life (1903), and The Sphere of Religion (1908).

In 1918 Frank and his second wife moved to New York City where his eldest daughter, Grace, had become an acclaimed singer of popular songs and operetta. Grace, a Smith College graduate, can be heard on early “talking machine records.” During World War I, she gave concerts to raise money for the troops and toured with the John Philip Sousa Band. Frank was devoted to Grace. Alas, she died of cancer in 1924, a very young woman.

Two years later Frank published a memoir, Tales of Hoffman. The book is a collection of stories. In its most engaging chapter, “Remarkable Animals I Have Known,” Frank returns to his summer on the Mississippi, 1870 . . .

After selling maps all day in Fort Madison, Iowa, Frank went out to supper and then started toward his hotel. He saw a big tent at the far end of a large green in the center of town. Approaching, he read a sign:

COME AND SEE THE EDUCATED PIG!

The tent was packed but Frank bought a ticket and squeezed in to see the show. Soon a retired schoolteacher named James Kelley limped out from behind a curtain, followed by a little white pig with a super-curly tail. His name was Pedro.

Kelley explained that the crowd could ask the pig any question as long as the answer involved numbers. The pig would demonstrate the correct answer using numbered blocks from a pile on the stage.

|

| Educated or learned pigs were popular attractions in the U.S. and Europe by the late eighteenth century. |

People began calling out questions; the answers included 1492, 1776, and 1870. A boy asked, “How old is my grandfather?” and the pig answered correctly: 81. And so it went until Frank, plotting to stump the pig—and presumably expose a fraud—stood up to ask three questions.

-When did the Turks

capture Constantinople?

-How old was Methuselah

when he died?

-Extract the cube root of 1728, multiply that by 72, divide by 36 and multiply the quotient by 13. What is the answer?

The pig answered each question correctly. Embarrassed, Frank returned to his hotel where he reflected darkly on how he would pay for four years of college and three years of graduate school. Then he contemplated Pedro the educated pig, who drew a crowd and earned money wherever he went.

Awakening at midnight Frank asked himself, “Oh, what’s the use? Oh, what’s the use?” That question may have been his

most profound contribution to the discipline of philosophy.

* Hoffman died in 1928.

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2022/10/tale-of-frank-sargent-hoffman.html