|

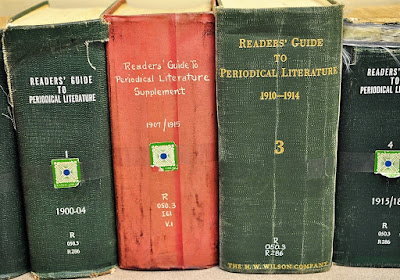

| The H. W. Wilson Company produced The Debaters Handbook Series between 1910 and about 1950. |

In 1907, a Minneapolis

publishing executive named Halsey W. Wilson was looking for writers and

researchers to work for his growing company.

Spurred by his wife, Justina, he asked a University of Minnesota

professor to recommend several alumnae. A

young woman named Edith Phelps left her teaching job and came on board right

away.

In short

order, Edith would become a supervisor and editor at the H. W. Wilson Company. She wrote dozens of guides to such topics as

the income tax, immigration, and the League of Nations.

These became known as “debaters’ handbooks,”

and were used by high school and college teams who sparred competitively about the

social policies and laws of the rising century.

But really, the handbooks had a larger significance. They were particularly useful to people who

lived in rural areas, with their reach extending well beyond debaters to men’s

and women’s clubs, voting leagues, and adult education programs.

In fact, making this literature widely

available tied into the Progressive ideal of educating as many Americans as

possible.

|

| Halsey W. Wilson (1868-1954) |

In 1913,

when Halsey Wilson decided to move his company to New York City, Edith Phelps

went with him. For the next 40 years,

she worked in the vanguard of what became known as information sciences. In 1922, she became an officer of the

company.

Back to the

other Edith.

Within

several years of Edith Penney’s arrival in New York, she made her mark on one

of the most innovative projects in the history of American education: The Eight-Year Study. This experiment posed a

challenge to the time-honored methods of evaluating college applicants long used

by admissions officials.

The study explored whether

students’ performance in the college preparatory curriculum was the best indicator

of college readiness and future success.

What would happen if students were to pursue an alternative high

school curriculum in the humanities and social sciences?

That

question lay at the heart of The Eight-Year Study, launched in 1930 by the Progressive

Education Association. That year, high school teachers and administrators started to

collaborate with researchers and college professors to revise the traditional

curriculum.

Between 1933 and 1940, 29

public and private high schools and 200 colleges and universities participated

in the experiment.

Along came

more classes in the manual and fine arts, a shift from survey-style courses to

electives that focused on a few texts or a historical era, and the elimination

of material that students had regurgitated since elementary school. There was a concerted effort to embrace unconventional

opinions and interpretations.

The outcomes

were positive. When it came to college

the Eight-Year Study students turned out to be as successful as students who

followed an established curriculum. They

also developed a wider range of interests outside the classroom.

As a high

school principal and member of two committees that directed the study, Edith

Penney became committed to educational reforms that would have been unheard of

during her Minnesota childhood.

Radical

as the work seemed during the 1930s, several of the ideas that emerged from The Eight-Year Study have endured.

|

| The Eight-Year Study was published in 1942 in five volumes. |

Professional

development for teachers, testing methods that would provide more accurate and meaningful

measures of students’ knowledge, and greater variety and student choice of

courses were among the changes.

High schools also began to push back against onerous college entrance

requirements.

Unfortunately,

the results of The Eight-Year Study received little attention when they were

published in 1942. Some critics thought

they were inconclusive while others feared change. Regardless, by

the time the war ended, school administrators were not in the mood to innovate. Every so often, however, the study draws

renewed attention.

Edith May Penney

retired in 1948 and died at the age of 96 in 1974.

Edith May Phelps

retired in 1948 and died at the age of 98 in 1980.

Continued

from post June 5, 2019.