Now

that the White House has celebrated Halloween, Melania Trump will retreat once

more to the second-floor family residence. Apart from the turkey pardon and Christmas parties, she probably will

appear infrequently in public until 2019.

From

the start, this First Lady has been unusually remote; socially and emotionally

unavailable to the American people. She

does not wish to conform to the modern conventions associated with the First

Lady, which emerged around 1902 during the Theodore Roosevelt administration.

Edith

Roosevelt became the first president’s wife to grant routine press coverage of

herself and her children. Such access increased

over time. During the past three

decades, as the media grew and the realm of First Ladies scholarship intensified,

historians have drawn ever greater attention to the role of the president’s

wife, raising expectations that the women will engage fully with the public.

But

now, nearly 20 months into the Trump presidency, we must conclude that the

First Lady is most interested in engaging with a very small circle of friends

and family.

Historically,

she is not alone. For antecedents, look to the dark, rainy first half of the

nineteenth century. One might not

recognize the names outright, for the women are obscure. Just like Melania

Trump, they were reluctant to leave the second floor of the White House.

The

women were Margaret Taylor, Abigail Fillmore, and Jane Pierce, three ladies who

never wanted their husbands to run for president and definitely didn’t care to

move to the capital city that was flourishing at the edge of a swamp.

|

| Margaret Taylor |

Not

everyone regarded the city with dread. By

1850, notwithstanding the summertime mosquitoes and damp winter chill in the

president’s house, Washington, D.C. captivated many a visitor. None other than

the vivacious Dolley Madison (wife of the fourth president) made things

sparkle. She hosted brilliant salons and encouraged the White House ladies who

followed her to step lively.

Dolley died in 1849, the year before Margaret Taylor arrived at the executive

mansion. But it mattered not to Margaret, Abigail

and Jane, who brushed off society and politics and participated in few White

House events.

To

be sure, they had reasons.

Margaret

grieved for her daughter, the first wife of Jefferson Davis, who died of

malaria while visiting Louisiana during “fever season.”

|

| Jane Pierce |

Jane

mourned the loss of her 11-year old son who died before her eyes in a train

accident less than two months before her husband was sworn in as president.

Abigail’s

health was poor.

In

turn, the three women stayed upstairs, read the Bible, and welcomed a few

friends to the parlor. They sent their

daughters and nieces downstairs to receive visitors and preside over dinners.

The

wives of presidents Taylor, Fillmore and Pierce were cast from the antebellum

feminine ideal that historians refer to as “the cult of true womanhood,” which

was fostered by a patriarchal system. The ideal virtues were piety, purity,

submissiveness, and domesticity.

|

| Abigail Fillmore |

Melania

Trump conforms, in part, to the type. Her adventures in modeling took her where

no First Lady has gone before, so one might cross off purity. Her manner is largely

compliant, however, and she prefers to be at home.

And

so there exists an odd affinity on the second floor of the White House.

On

one hand, here is a woman who owes her rise to the twenty-first century’s lack

of inhibitions. On the other hand, there

are three Victorian ladies dressed in black gowns with stiff lace bodices, bent

over their embroidery and asking for smelling salts.

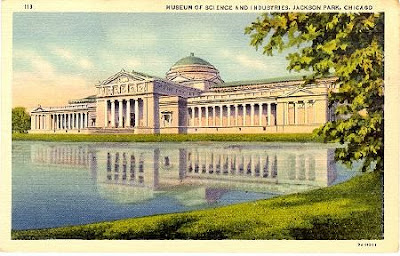

|

| Antebellum White House |

Melania montage by Claudia Keenan

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2018/10/the-first-lady-is-upstairs-today.html