|

| "Manhattan: Central Park - The Majestic Apartments" (New York Public Library Digital Collections) |

When my mother was a student at Hunter College during the late 1940s, she routinely traveled south on the A train from her family’s apartment in Inwood, a neighborhood at the tip of northern Manhattan.

She’d get on at 207th Street and ride until 72nd Street. Then she would transfer to a crosstown bus to the East Side, where Hunter is located.

Walking by the luxurious Majestic, one of several Art Deco apartment buildings that had been built along Central Park West around 1930, my mother often spied a violet-colored Cadillac waiting at the curb. One day she asked the doorman to whom it belonged and he told her “Mr. Costello.” That was Frank Costello, the mobster who lived upstairs.

Ten years later, in May

1957, Costello would survive an assassination attempt in the Majestic’s lobby. A

few months went by before the FBI and the New York City police homed in on the

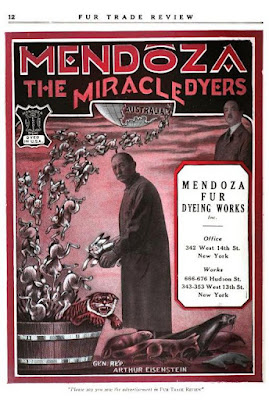

shooter: an “ex-pug”—pugilist—known as “the Chin.” He was Vincent Gigante, acting

on behalf of the Genovese family.

The 25-year old Gigante wore a size 50 suit and waddled when he walked. Some newspaper accounts referred to him as “the Waddler” rather than “the Chin.”

Gigante, his wife, and four children lived downtown on Bleecker Street. The detectives staked out his house around the clock. Yet Gigante eluded them until one August afternoon when he showed up at the West 54th Street police station (accompanied by his lawyer). “Do you want me in the Costello case?” he asked.

“We sure do,” said Deputy Inspector Fred Lussen. But Gigante would not cooperate, refusing to answer questions.

I explained this to my

mother and she smiled and nodded. She wouldn’t have been paying attention in

the spring of 1957 because she had a brand-new bouncing baby boy, my older

brother.

|

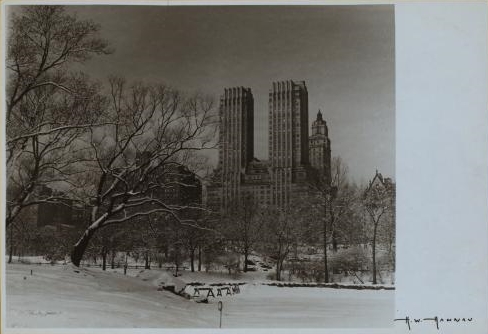

| 1931 Dyckman Street shooting |

Then I told her that she’d had a closer brush with gangsters up there in Inwood in 1931 when she was three years old. It turns out that another three-year old girl, also named Gloria, was shot to death at the end of a 90-minute gun battle between the police and two robbers.

|

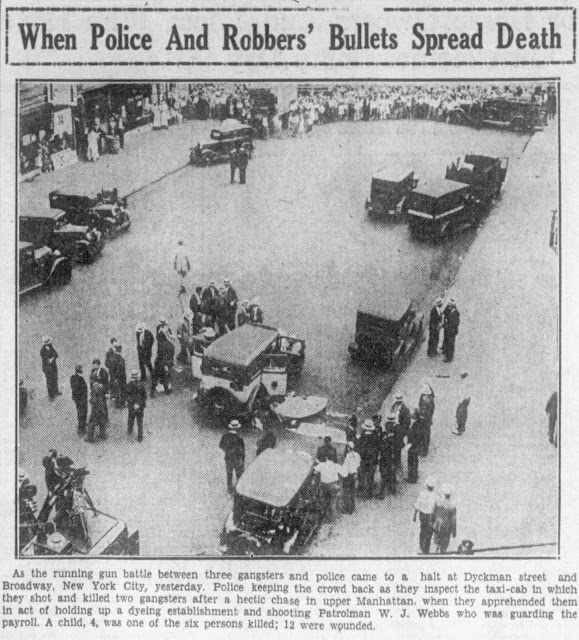

| Advertisement for Mendoza Fur Trade Review, 1931 |

Just before 5 o’clock on a warm Friday afternoon, a policeman escorted the paymaster of the Mendoza Fur Dyeing Company, who carried a payroll of $4,619 from a bank, through the plant’s parking lot. Two robbers approached the car and shot the policeman and threw the paymaster on the ground.

Then they led a chase that ranged along twelve miles of streets in upper Manhattan and The Bronx. Six people would die, both patrolmen and bystanders who were starting the weekend a few minutes early as the season wound down toward Labor Day. The youngest victim was little Gloria Lopez, whose mother Matilda told reporters that she and her husband, a fireman, had tried for a decade to have a baby.

| The story made it into the Great Falls, Montana newspaper. |

The chase finally ended near the corner of Dyckman Street and Broadway in Inwood, an intersection that remains a touchstone of my mother’s childhood memories.

She was too young to remember playboy Mayor Jimmy Walker, who presided over the city. At the time of the shootings, Walker was traveling in Europe because New York State Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt had appointed a commission which threatened to investigate the Tammany Hall corruption that Walker enabled.

|

| Meantime, Mayor Jimmy Walker was in Germany "for his health." |

In this way Walker resembled previous mayors beholden to Tammany. But his indifference to the robbery and deaths—which inspired the American Legion to offer to mobilize 30,000 members to patrol the city with bayonetted rifles—was exceptionally offensive.

“Being 3,000 miles from New York,” Walker told reporters, “I am ignorant of the circumstances of the shooting. I cannot give any opinion.” Then he was off to a brewery in Pilsen, whose mayor announced that Pilsen beer was not only an excellent but sanitary drink.

Jimmy Walker quaffed a stein and commented that none of the cathedrals or museums he had visited in Europe gave him greater pleasure than the beer. He hoped that the Pilsener sign would soon return to New York, he said.

|

| My mother, Gloria (left), with an Inwood playmate, 1931 |

It would be two more years before the repeal of Prohibition. In the meantime, Governor Roosevelt forced Walker to resign and my mother continued to toddle around up and down Dyckman Street, holding her mother’s hand. It could have been her caught in the crosshairs, but then I wouldn’t be telling this story.

*In 1933, Mr. and Mrs. Lopez became the parents of John. Jr.