|

| Herma Wager around 1919 |

Herma was the fourteenth

of fifteen children born to Robert and Harriet Wager of Ohio.

Just after the American Civil War ended, Rob, as he was called, left his childhood home in Parham, Canada. He traveled 500 miles along lakes Ontario and Erie to reach Toledo, Ohio. Then he pushed forty miles farther west to Stryker, a railroad town incorporated in 1855.

Within a few years he met Harriet Justus of Defiance, Ohio, and they wed in 1869 when she was sixteen and he twenty-three. His older sister, Jen, who stayed in Canada, seems to have never recovered from Rob’s departure nor those of anyone she knew—whether to the blur of America or to heaven.

In a series of small, black-edged letters, which arrived in black-edged envelopes addressed in her spidery script, Jen grieved for twenty years. The worst was Ma, in 1881:

I miss her every place I look, I can see

something to remind me of her something that she has made or fixed and it seems

almost more than I can bear, I am alone so much, too, Pa and Hiram are in at

mealtimes and evenings and the rest of the time I am alone. I think if I had

someone to talk to and keep me from thinking it would not be so hard.

One year later Pa, his eyes streaming with tears, took to his bed and never got out. Next to go were the pretty, young schoolmarm and the neighbors’ children.

Thus there was always bad news from Jen except when she went overnight to Kingston and bought new trimmings to fix up an old dress.

It’s not that death didn’t follow Rob to Ohio.

Herma came along in 1896, more than a decade after her sisters Estella, Florence, and Luella, her brother Charles, and a baby boy who didn’t live long enough to be named, had passed.

By now the family had moved to Wauseon, where Rob no longer worked as a farm laborer but as a section foreman for a manufacturer of plumbing equipment.

In Wauseon the houses

marched up and down the street, close together with picket fences between them and

front porches where friends gathered. The turn of the century approached and

the family felt happy. In 1900, when Harriet was forty-seven years old, she

gave birth to her last child, George.

|

| The Wager family in Wauseon, early twentieth century. Herma sits to her mother's right and Bob stands, far left. |

But the happiness fled. Rob died in 1901 and George died in 1902. He caught typhoid fever from his brother Clyde but Clyde recovered and George—dear baby, he was just starting to talk.

“Oh we miss him so much,” Harriet wrote to Jen, still brooding in Canada. She put on her own black costume and wore it for the rest of her life.

Herma had never been a smiling kind of person but now, when the camera captured her out in the yard in a white voile dress, she looked distant and sad. Only the sight of her brother Robert, whom she adored, could cheer her.

|

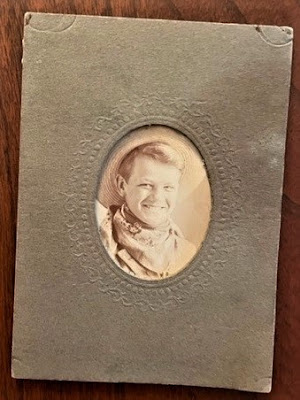

| Bob Wager dressed as a cowboy |

Bob, as they called him, was Herma’s favorite among the Wager brothers: Warren, Sheldon, Foster, Clyde, Elwood, and Floyd. Three years older than Herma, Bob was her protector and comforter, her imp who became a handsome, responsible young man.

He left home in his late teens, moved to Cleveland and worked for the Willard Storage Battery Company, an early manufacturer of automobile ignition batteries. Around 1912, amid skyrocketing demand from car companies, Willard opened plants in Atlanta and Huntsville. Bob was assigned to the latter.

The U.S. entered World War I in April 1917, and three months later Bob enlisted in the Naval Aero Service. He trained at Pensacola, the nation’s sole naval air station, as a flier and mechanic.

|

| R-6 Seaplane, Pensacola, 1917 (National Museum of the American Navy) |

Aviation was still primitive. In the U.S., military officers planned to use planes for observational purposes rather than in combat. Of course, this view changed quickly when the generals got to Europe. Still, the U.S. never kept up with the allies’ aviation capabilities.

Bob arrived at the newly established U.S. Naval Air Station in Moutchic, France in December, and within six weeks he died of cerebrospinal meningitis. Many enlisted men were struck down by tuberculosis, pneumonia, and meningitis even before the influenza became a pandemic. Bob’s story is not unusual, perhaps only to the extent that he was the first Wauseon boy to die in the Great War. He is buried in France.

In 1920 Herma married William Carroll Keenan, a veteran who went by “Cal” during that particular heyday of nicknames. They had two sons, Bill and Bob, both of whom recalled an impersonal, detached mother. They couldn’t get away from her fast enough.

When Bill and Bob grew up and married, their wives disliked Herma, too. The grandchildren found her visits uncomfortable.

So what of Herma? No one has spoken of her for a half-century or more. There is little reason to tell her story to each new generation, to make sure her name and face are imprinted in the minds of her descendants.

Still she demands some understanding, my husband’s disagreeable grandmother.

I think that Herma may have suffered from untreated post-partum depression. And she never recovered, even partway, from her brother Bob’s death nor that of little George who toddled around the farmhouse and probably was her charge.

Perhaps she saw Bob and George in the faces of her own sons but could not summon for them the same depth of feeling. It may be that everything that lived and laughed for Herma was back, way back before the twentieth century inflicted its blows.

|

| Harriet Justus Wager died in 1918. As Herma grew older, she came to resemble her mother. |

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2023/02/understanding-herma.html