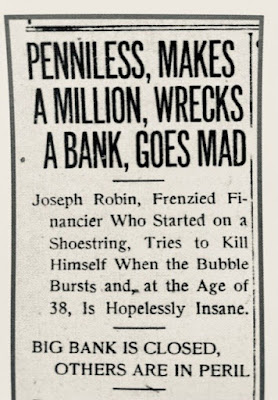

Thursday, December 15, 2022

Wednesday, November 9, 2022

Chasing Charles Hemstreet

|

| Charles Hemstreet, 1900s |

Up in Buffalo, N.Y., Lake Erie narrows like a funnel into the Niagara River. Even before the Erie Canal opened in 1825 and through the nineteenth century, a shipbuilding industry flourished on the American side of the river.

Charles Hemstreet’s father, William, was a Buffalo ship carpenter who helped build some of the steamers that plied Lake Erie carrying freight and passengers. William’s oldest son, Felix, became a ship carpenter’s apprentice at the age of fourteen.

But Charles, born in 1866, had greater aspirations. Although he advanced no farther in school than sixth grade, Charles loved to read newspapers and books about history. Around 1885, he went south to New York City to look for a job that would suit his interests.

During these years, the

city was home to at least fifteen daily English language newspapers. Charles worked

as a police reporter at a time when the department was at its most corrupt. The

job required much hanging around headquarters on Mulberry Street. Charles

stayed a few years, then became night manager of the Associated Press, a

position he held for a decade.

|

| New York City Police Headquarters, 1890s when Theodore Roosevelt was Commissioner |

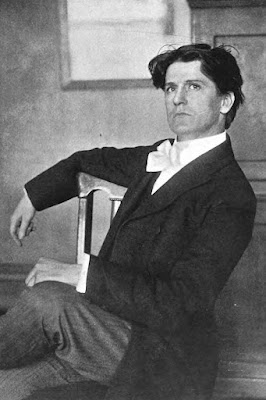

Everything seemed to come his way, this foppish young man with a poet’s hair, dark and wavy, who liked to assume dramatic poses.

An officer of the New York

Press Club, Charles often visited a shaky old building on Spruce Street, off

Newspaper Row near City Hall Park, to carouse with fellow members of the

notorious Blue Pencil Club.

|

| Blue Pencil Club members at play |

He’d bound up and down the stairs with a bunch of mischievous, irreverent reporters, editors, writers, cartoonists, and illustrators. They published a bawdy short-lived magazine and ran all over town drinking and declaiming.

Charles’s wife, Marie Meinell, daughter of a grumpy Civil War veteran from Oyster Bay, also joined the Blue Pencil Club. Not only did Marie qualify as a published author (of insipid poetry), but she was mischievous, too.

In 1893, quarantined in a hospital with scarlet fever, Marie decided to escape by sliding down a rope to the street. Traveling under the name “Edith Fish” because she thought she might be sent to prison for running away, Marie raced off to Jersey City and Philadelphia. Finally she made her way to the Adirondacks where Charles came to comfort her and presumably did not catch scarlet fever.

Charles was just 34 when he announced his retirement from journalism. According to a widely published notice, he would now devote himself to writing books. His first one, Nooks & Corners of Old New York, was published by Scribner’s in 1899, followed by The Story of Manhattan (1901), When Old New York was Young (1902), and Literary New York (1903).

But Charles couldn’t just

sit around and write books. One day he was called to the scene of an excavation

for the subway in lower Manhattan. Italian immigrant laborers had unearthed a

stone from a Revolutionary War fort. He told a Times reporter:

I understand that the contractor is

preparing to present the slab to the New-York Historical Society. I will do all

I can to prevent this. Once in the possession of the society it would be as

inaccessible to the general public as though it had been left in its

underground resting place.

He was correct. And how delightful to be regarded as an expert on old New York, long the domain of patricians with trailing pedigrees.

In 1906, Charles and Marie sailed to Europe to collaborate with Jeannette Pomeroy on a scientific study of the appearance of American women. Mrs. Pomeroy, an English woman descended from Indian occultists—she said—was widely admired for her beauty advice and business acumen. The New-York Tribune reported:

If Mrs. Pomeroy is right in her conclusions

that the women of America are growing less beautiful year by year, she will

invoke national, state and municipal governments to aid her in forcing women to

become beautiful whether they will or not.

The remedy for the dearth

of beautiful women, Charles said in a statement, “is to simply surround women

with delectable odors, dulcet sounds, palatable foods, beautiful sights, and

correct ideas.”

|

| Mrs. Jeannette Pomeroy |

I was sorry to learn that

Charles dealt in such sexist foolishness because he’s so likable otherwise.

Enmeshed in a lawsuit that would result in the loss of her cosmetics empire, Mrs. Pomeroy faded from the scene while Charles and Marie stuck around to research a book, Nooks and Corners of Old London. Once back in the U.S., Charles accepted the position of manager of Burrelle’s Press Clipping Bureau. He had found a new career.

Nelle Burrelle deserves her own novel. It suffices to say she was an adventuress. When Louis Chevrolet invited her to race with him, they circled the 1-1/2 mile Morris Park Racetrack in 53 seconds. Shortly before her own mysterious death, she flew around in a Curtiss airplane above Mineola Field on Long Island.

|

| Nelle Burrelle, 1910 |

In 1911 Nelle fell ill at

her apartment in the Carlton Hotel on 44th Street and was attended

for several days by three physicians, including Dr. Jesse W. Amey whose

romantic advances she had spurned after her husband’s death. The physicians

listed acute nephritis as the cause of death but the coroner received an

anonymous tip that Nelle had been murdered. He performed an autopsy and ruled

her death to be of undetermined cause.

|

| Burrelle's advertisement, about 1915 |

The date and Nelle’s signature

were missing, rendering the will invalid. Unsurprisingly, given the shady

story, someone leaked its contents: 16 shares of Burrelle Clipping Bureau stock

to Charles Hemstreet, $2,000 to Marie Hemstreet, a few shares to various

employees and relatives, and the balance to Dr. Jesse W. Amey.

One year later, the same surrogate approved a different will for probate. It split the estate between Nelle’s two sisters. And that was that.

If Charles Hemstreet was left out in the cold, he carried on at Burrelle’s and drew income from his books, which continued to be popular with the exception of a novel, The Don Quixote of America, the Story of an Idea, published in 1921.

The book stars John Eagle of upstate New York, who dreams of building a new city in the western wilderness and travels by train to Los Angeles. There, nothing goes his way. He is beaten up and the butt of jokes. Upon his return home, however, he is greeted with fanfare and hailed by his friends and family.

One critic wrote:

The jacket hints of an “underlying idea.” I

have spent weary nights over the home brew trying to excavate it. I leave it

for future literary archeologists to unearth.

Charles Hemstreet of America, an idea for a story.

*Charles Hemstreet died in

1941 and Marie in 1943.

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2022/10/chasing-charles-hemstreet.html

Wednesday, October 5, 2022

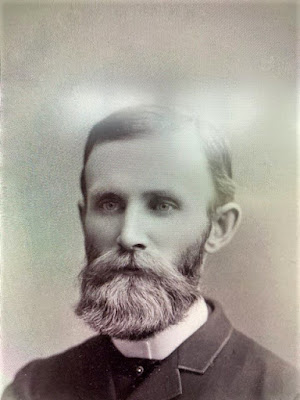

Tale of Frank Sargent Hoffman

|

| Frank Sargent Hoffman Professor of Moral and Mental Philosophy, Union College, N.Y. |

Consider the situation of Frank Sargent Hoffman, casting about for work after a railroad job fell through.

Born on a ranch in Wisconsin in 1852, Frank came from a long line of farmers, a

profession he did not want.

He was about 17 years old, with his heart set on becoming a brakeman and rising to the position of conductor. But the distant relative who promised to use his influence changed his mind.

Now here was Frank in the

summer of 1870, traveling along the west bank of the Mississippi River, Dubuque

to St. Louis and back again, hoping to make some money. Frank wasn’t selling cloth,

coffee, tea, boots or dried figs.

|

| Mississippi River where it passes Iowa and Missouri |

No, he peddled just one item: a map that depicted the Franco-Prussian War, created by a friend in Chicago. Frank had dozens of copies in his knapsack, each available for 25 cents to the people of Davenport, Muscatine, Burlington, Keokuk, and so forth.

The maps were popular and Frank often telegraphed his friend in Chicago asking for more to be sent to the express office closest to wherever he happened to be along the river.

|

| Stylized map of the Franco-Prussian War, 1870 (not the one Frank sold) |

Better to be navigating those towns in the summer heat than be caught in the Siege of Metz, which would begin that same August and end in October with Alsace-Lorraine in the grip of the German Empire.

At the close of summer, Frank retreated to Galesburg, Illinois, where he lived with his father and mother and two sisters. After leaving Wisconsin, the family had eventually landed in Galesburg, where they continued to farm.

Galesburg has a few claims to fame. The poet and Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg was born and grew up there. It is also the home of Knox College, founded in 1837 by a group of Protestants and Congregationalists. In the fall of 1870 Frank entered Knox, where he studied for two years before transferring to Amherst College.

Subsequently, Frank

graduated from Amherst, earned a Master of Divinity and a PhD at Yale, studied

in Germany with the philosophers Zeller and Fischer, and became a Professor of

Mental and Moral Philosophy at Union College in Schenectady, New York.

|

| Union College entrance, early twentieth century |

In 1885, when Frank

arrived at Union College, the school was at its nadir. The student body and

faculty had shrunk, and those who remained lacked morale. An interim president,

Judson S. Landon, was surely more preoccupied with his position as a justice of the

New York Supreme Court.

The Union College website refers to “17 years of unrest and stagnation,” which would constitute a devastating setback for any institution. The story is buried in the college's archives.

Frank Hoffman didn’t save the day but a new president, Harrison Edwin Webster, is said to have improved the mood and tripled enrollment. However, Webster and the presidents who followed him did not like “Hoffy.” Frank’s popularity with students—especially Phi Gamma Delta—may have worked against him. Efforts to ease him out started in 1889 but he managed to hang in until 1917. During those years he published four very dry books: The Sphere of the State (1894), The Sphere of Science (1898), Psychology and Common Life (1903), and The Sphere of Religion (1908).

In 1918 Frank and his second wife moved to New York City where his eldest daughter, Grace, had become an acclaimed singer of popular songs and operetta. Grace, a Smith College graduate, can be heard on early “talking machine records.” During World War I, she gave concerts to raise money for the troops and toured with the John Philip Sousa Band. Frank was devoted to Grace. Alas, she died of cancer in 1924, a very young woman.

Two years later Frank published a memoir, Tales of Hoffman. The book is a collection of stories. In its most engaging chapter, “Remarkable Animals I Have Known,” Frank returns to his summer on the Mississippi, 1870 . . .

After selling maps all day in Fort Madison, Iowa, Frank went out to supper and then started toward his hotel. He saw a big tent at the far end of a large green in the center of town. Approaching, he read a sign:

COME AND SEE THE EDUCATED PIG!

The tent was packed but Frank bought a ticket and squeezed in to see the show. Soon a retired schoolteacher named James Kelley limped out from behind a curtain, followed by a little white pig with a super-curly tail. His name was Pedro.

Kelley explained that the crowd could ask the pig any question as long as the answer involved numbers. The pig would demonstrate the correct answer using numbered blocks from a pile on the stage.

|

| Educated or learned pigs were popular attractions in the U.S. and Europe by the late eighteenth century. |

People began calling out questions; the answers included 1492, 1776, and 1870. A boy asked, “How old is my grandfather?” and the pig answered correctly: 81. And so it went until Frank, plotting to stump the pig—and presumably expose a fraud—stood up to ask three questions.

-When did the Turks

capture Constantinople?

-How old was Methuselah

when he died?

-Extract the cube root of 1728, multiply that by 72, divide by 36 and multiply the quotient by 13. What is the answer?

The pig answered each question correctly. Embarrassed, Frank returned to his hotel where he reflected darkly on how he would pay for four years of college and three years of graduate school. Then he contemplated Pedro the educated pig, who drew a crowd and earned money wherever he went.

Awakening at midnight Frank asked himself, “Oh, what’s the use? Oh, what’s the use?” That question may have been his

most profound contribution to the discipline of philosophy.

* Hoffman died in 1928.

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2022/10/tale-of-frank-sargent-hoffman.html

Wednesday, September 7, 2022

Oddments of Clara & William Sulzer

|

| Clara Sulzer, around 1910 |

What is left of Clara and William Sulzer?

Scraps of silk and velvet, feathers, flowers—trimmings for Clara’s outré hats . . .

The yellowed newspaper clippings about William's impeachment by the New York State Legislature . . .

. . . and the usual Albany gossip perpetrated by the Tammany Hall Sachems.

Governor William “Plain Bill” Sulzer was born in 1863 in New Jersey, to a Frisian* mother and German father, and reared on Manhattan’s Lower East Side.** There he imbibed machine politics at a young age.

Sulzer was a brilliant debater and orator who cultivated his physical resemblance to Henry Clay. Like Clay, he hoped to become President of the United States.

In the 1880s, having attended Columbia Law School, Sulzer became a protégé of Tammany Hall boss John Reilly. He bounded into the New York State Assembly, rising to the position of speaker, but set his sights on the House of Representatives. Sulzer would represent the Tenth District—largely Eastern European immigrants—for nine consecutive terms.

|

| Governor Sulzer soon after his election |

In Congress, Sulzer sponsored progressive legislation: creating an independent Department of Labor, setting an eight-hour workday for federal employees, publicizing campaign contributions. As chair of the Foreign Relations Committee, he endeared himself to Jewish voters by pushing for abrogation of an 1832 U.S.-Russia treaty that established reciprocity among citizens with passports.

The treaty was a problem

because Russia had been denying entrance to American Jews and, to a lesser

extent, Protestant missionaries and Catholic priests since the 1870s. The successful

campaign for abrogation was led largely by the American Jewish Committee and

the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

Meanwhile, in Philadelphia, Sulzer’s future wife Clara Rodelheim was growing up in an Orthodox Jewish family. Her father, Max, was in manufacturing or possibly a liquor dealer.

Clara became a nurse after attending the New York City Training School and might have met Sulzer in 1904 when he toured a Manhattan hospital. Or he might have fallen in love with her while he was a patient at the hospital and she his “tender and sympathetic” nurse.

It may be that they met at a dinner party in Washington, D.C. in 1904. When he saw her again in 1908, he said, “Don’t you think it is time we were getting married? You know we have been engaged for four years.”

These various tales appeared in newspapers. Once upon a time, public figures could get away with competing stories.

Much to the surprise of the Rodelheim family, Clara and Sulzer were married quite suddenly in the parsonage of the First Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia.

“We don’t want the wedding to have any publicity just now,” one of Clara’s sisters told a reporter at the door, pushing her chatty mother out of the way.

In July 1913, a Wanamaker’s saleswoman named Mignon Hopkins sued Sulzer for damages. She alleged that Sulzer had proposed to her in 1906, that she had passed as his wife on several occasions, and that there were love letters. Sulzer, she claimed, had ruined her life.

“Nothing to it,” Sulzer told the newspapers. Indeed, it was the least of his troubles. He knew what was coming.

Sulzer was elected New York Governor in 1912. He owed a great debt to Tammany but announced that he would be a reformer, independent of the machine. He pledged to “clean house” and called for honest, efficient government. For example, he demanded investigations into the prison system and the cost of rebuilding the burned-down state capitol building.

|

| The Great Capitol Fire, March 1911 |

Tammany pushed back immediately in the form of the Frawley Committee, which announced its findings in August 1913. Sulzer was charged with making false statements, using campaign funds to invest in stocks, and violations of the New York Corrupt Practices Act. The committee announced it would pursue impeachment. Everything happened quickly.

From the 2 a.m. shadows stepped Clara, claiming that she alone had invested campaign funds in the stock market. In fact, she had forged her husband’s signature, she confided to the minority leader, a Democrat. She produced a chart that purported to show the money trail. Then she went into hiding and her doctor issued bulletins about nervous collapse, prostration, and grave illness.

|

| In 1913, Mrs. Sulzer was the first recipient of a parcel post package on the New York City to Albany route. |

While Clara lay in bed,

the French newspapers became obsessed with the case. The Journal des Débats commented

curiously on the Governor’s wife and American culture:

This news deserves attention, as it shows a

revolution in American conjugal life. Hereto our conception of the husband has

been that of a breadwinner, a money maker and a check signer, happy with the

fact that he was able to supply his wife with money to rain dollars in Europe,

while we thought she ignored the origin of the dollars and often was almost

unable to say what her husband’s profession was. We must now renounce this

prejudice before Mrs. Sulzer’s detailed statement. Such accountantlike

precision would be affecting anywhere but in New York it is sublime.

After Governor Sulzer refuted Clara’s confession, the investigative committee promised more revelations and Sulzer tried to bargain personally with Frawley. The vote was 79-45 to impeach.

Sulzer left office in October 1913 but within weeks he ran as an Independent to represent the Sixth District in Manhattan, which was 80 percent Jewish. Purportedly, six rabbis implored him to enter the race, which he won.

After serving one term in the state legislature, Sulzer moved with Clara to a small house on Washington Place. Incredibly, when he died in 1941 there were no obituaries in the New York papers.

Only the Times acknowledged him with a few paragraphs on the editorial page, which began:

William Sulzer may be said to have been a ghost long before

he died.

|

| The ghost of Clara Sulzer |

*The

Frisian Islands are an archipelago along the coasts of Germany, the

Netherlands, and Denmark.

**He may have grown up on his

parents’ farm in Elizabeth; accounts vary.

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2022/09/oddments-of-clara-william-sulzer.html

Thursday, August 4, 2022

Wednesday, July 6, 2022

Uncovering Joseph G. Robin (part 2)

|

| Joseph G. Robin on the way to jail |

In January 1913, fallen

far from grace, New York financier Joseph G. Robin was sentenced to one year at the New York City

Penitentiary on Blackwell’s Island, a narrow island in the middle of the East

River, which is now called Roosevelt Island.

How much had Joseph embezzled? Reports ranged from $10,000 to millions. The amount mattered, of course, but it was the light sentence that drew the public’s outrage.

|

| The Queensboro Bridge crosses Blackwell's Island, renamed Welfare Island in 1921 and Roosevelt Island in 1973. |

Hoping for leniency, Joseph had dropped his initial plea of insanity and cooperated with the D.A. He implicated a former city official and two Carnegie Trust bankers in bribery schemes involving the investment of city funds.

Joseph entered the penitentiary on a mild spring day. Once on the inside, overcome with a desire to clear his name, he requested and received a pardon from New York Governor Sulzer. But the pardon would be ruled invalid because Sulzer was in the midst of an impeachment trial.

|

| New York State Governor William Sulzer, who cultivated a resemblance to Henry Clay. |

After his release, Joseph received a pardon from the new governor and testified further about bribery in the railway business. Then, it seemed, he disappeared from the record.

But the internet agreed to be prodded and finally gave Joseph up. His name appeared on a list of deaths that occurred during April 1929, information that unlocked what may be the most interesting part of the story of Joseph G. Robin.

It turns out that the American novelist Theodore Dreiser (1871-1945) met Joseph in 1908 when the banker was nearing the peak of his wealth and influence. By that time, Dreiser, a native of St. Louis, had published at least a dozen short stories as well as Sister Carrie, one of several novels he would write about strivers who rise high and fall hard.

|

| Newspaper illustration of Theodore Dreiser, around 1908 |

Dreiser, like Joseph, was sitting on top of the world. As editor-in-chief of Butterick Publications, which owned three women’s magazines—The Delineator, Designer, and the interestingly named New Idea Women’s Magazine—Dreiser mingled with the likes of President Theodore Roosevelt and H.L. Mencken. He and Joseph took to galivanting around town. They hit it off because, scholars have written, both men were the children of immigrants, had bouts with mental illness, and overcame adversity to achieve success.

|

| Joseph G. Robin's estate, Driftwood Manor, once located in Wildwood State Park on the north shore of Long Island. https://liparks.com/the-hidden-past-of-wildwood-state-park/ |

Dreiser found inspiration

in Joseph’s life. When he sat down to write Twelve Men (1919), a

collection of largely biographical stories about men he had known, he based “’Vanity,

Vanity, Saith the Preacher” on the life of Joseph G. Robin, referring to him as

“X.” Here, Dreiser recalls a visit to Joseph’s Long Island mansion:

He was always so grave, serene, watchful

yet pleasant and decidedly agreeable, gay even, without seeming so to be. There

was something so amazingly warm and exotic about him and his, and yet at the

same time something so cold and calculated, as if after all he were saying to

himself, “I am the master of all this, am stage-managing it for my own

pleasure.”

At the end of “Vanity, Vanity,” Dreiser defends Joseph:

. . . the man had been a victim of a cold-blooded conspiracy, the object of which was to oust him from opportunities and to forestall him in methods which would certainly have led to enormous wealth.

The men stayed in touch after

Joseph’s release from prison. Dreiser encouraged Joseph to write, and during

the 1920s the former banker published two plays under a pseudonym. But it

appears that his real talent was double-dealing.

|

| Joseph G. Robin easily made it into Volume II of Henry Ford's 1921 compilation, The International Jew. |

*Dreiser also drew on Joseph G. Robin’s personality for the character of Frank Cowperwood in The Financier (1912).

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2022/07/shalom-joseph-g-robin-part-2.html

Friday, June 3, 2022

Discovering Joseph G. Robin

|

| Joseph G. Robin, early twentieth century, newspaper illustration |

Joseph

G. Robin was a New York banker who became very wealthy during the Gilded Age. He amassed

and developed real estate, built a web of railways, and made a few shady deals

with power companies that sprang up in the spray of Niagara Falls.

But it was Joseph’s consolidation of banks, from which he had embezzled mightily, that finally caught up with him. Everything fell apart on December 28, 1910, in the midst of a state investigation of insurance companies. Joseph was arrested and put in the Tombs, a damp crowded prison designed to look like an Egyptian mausoleum, located in lower Manhattan.

Evidently Joseph anticipated the arrest, because he tried to commit suicide by jumping from a window in the Beaux-Arts Building, where he lived several floors above the Café des Beaux-Arts. Further, his friends told reporters, he flaunted a packet of cyanide.

Joseph’s older sister, Louise, was a physician dedicated to improving the medical treatment of inmates in prisons and asylums. She managed to whisk her brother out of the Tombs and hired three alienists to examine Joseph and commit him to a sanitarium. Within a day or two, however, a judge declared Joseph sane, impaneled a grand jury, and sent him back to prison.

Facts and rumors tumbled forth. Joseph and Louise had emigrated from Russia to the U.S. in the 1880s, the children of Herman and Rebecca Rabinovitch. Joseph changed his surname to Robin when he was quite young although Louise remained “Rabinovitch.” Joseph earned his first dollars selling a story to the newspapers. It concerned the scandalous conditions that his sister uncovered in the course of her medical investigations.

|

| Newspaper sketch of Louise Rabinovitch |

Joseph insinuated himself into Wall Street, investing in various schemes. By the mid-1890s, now a popular financier who pranced around town, Joseph courted wealthy widows and touted his French blood. He pronounced his name “Ro-ban” and thought he had left the past well behind.

Then detectives turned up an elderly Jewish couple who claimed to be the parents of Joseph and Louise. They were brought to the courtroom to see their son, but he and his sister insisted that these people were not their parents. Speaking in broken English, weeping and wailing, the mother gave the District Attorney letters that Joseph and Louise had written to her and her husband. One was dated August 31, 1892.

My Dear Parents: Please

answer me at once if I can have anything of you, or something of you, or

nothing. . . I need $10 for a ticket and $15 for two or three weeks’ board and

lodging. Please answer at once: don’t wait for a minute and send me the money or

write me one word, “not.” Remember this only that if you refuse me I will have

nothing in common with you! Your son, Joseph

Joseph and Louise were adamant that they did not know Herman and Rebecca and refused to speak with them. Perhaps the couple were opportunists but I doubt it. They died a few years after their son was sentenced to one year in prison.

According to reports, Joseph spent his time at the Tombs in an office—not a cell—equipped with a telephone and typewriter. There he carried on, working with his brokers, trading stocks and bonds; mixing despondency and defiance.

|

| Postcard of the Tombs, early 1900s |

To be continued.

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2022/06/discovering-joseph-g-robin.html

Thursday, April 7, 2022

Comstock

|

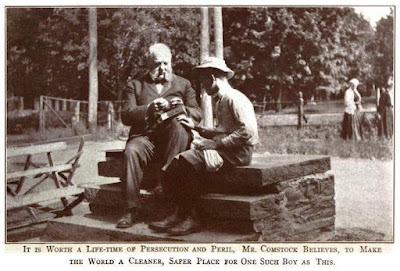

| Illustration from Anthony Comstock, Fighter by Charles Gallaudet Trumbull (1913) |

Attempts by state legislatures

to prevent women from procuring Misoprostol and Mifepristone through the mail

recall old times in a deeply concerning way.

Those were the days of Comstockery.

Anthony Comstock (1844-1915), who spent more than forty years persecuting Americans for engaging in activities that he deemed obscene, started his career in 1873 when he suppressed an “objectionable” book in the store where he worked as a clerk.

That year he established the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and became the unpaid enforcer of the Comstock Laws, which he had persuaded members of Congress to pass with alacrity.

The Comstock Laws criminalized the possession and conveyance of lewd, lascivious, filthy, indecent and disgusting material and objects. Those words actually appeared in the Federal Criminal Code, Section 211, from which all Comstock Laws descended.

Thus the United States

Post Office was among the private and public institutions, organizations, and

businesses—including an old bookstore which stocked antique porn—that fell

under the control of Anthony Comstock, special agent for the postal service.

|

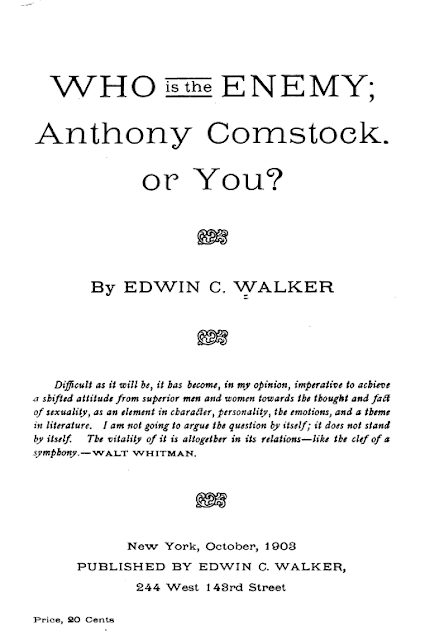

| Comstock was not without his detractors. |

Right up until 1914, the year before he died, Comstock initiated 3,697 state and federal arraignments of Americans whose behavior and/or possessions he found obscene. Of these, 2,740 pleaded guilty or were convicted.

Information about birth

control—“prevention of conception”—fell into that category, as discovered by

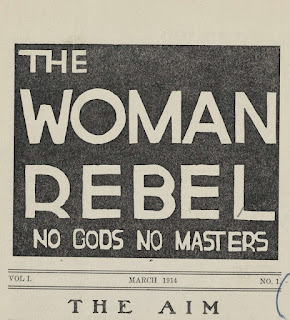

Margaret Sanger, an advocate for reproductive rights who published and

distributed a newspaper, The Woman Rebel. Sanger, a nurse and social

worker who lived in New York City, was especially concerned about the plight of

working-class women who lacked information about how to prevent pregnancy and any way to get safe, effective contraception. Meanwhile, she argued, wealthy

women had access to whatever they needed.

|

| Masthead of The Woman Rebel |

After Sanger mailed out three issues of The Woman Rebel, Comstock became enraged. In August 1914, he had her indicted for violating the law but she was released without bail and fled to England. In Sanger’s absence, her friends distributed 100,000 copies of Family Limitations, a brochure about contraception.

|

| Newspaper story, April 1914; "Make P. O. Officials Blush" |

Subsequently, one of Comstock’s agents tricked Sanger’s husband, William, into handing over several brochures upon request. William Sanger was indicted and convicted and sentenced to thirty days in prison.

“The sooner society gets rid of you the better!” one of the judges proclaimed from the bench.

When Margaret Sanger returned to the United States in 1915, she, too, stood trial. After her five-year old daughter died of pneumonia, the charges were dismissed. She went on to found the nation’s first birth control clinic and crusaded for reproductive rights until her death in 1966.

The Comstock Act has not been enforced for over fifty years. But it still smolders, awaiting a spark.

It is time for the people of this country to find out if the United States mails are to be available for their use, as they in their adult intelligence desire, or if it is possible for the United States Post Office to constitute itself as an institution for the promulgation of stupidity and ignorance, instead of a mechanical convenience.

--Margaret

Sanger

|

| Newspaper sketch, 1880s |

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2022/04/comstockery.html

Conjuring Jane Pierce

Imagine Jane Pierce in her black gown and mantilla. She sits on a slipper rocker in her second-floor bedroom in the White House. Clutching...

-

Postcard of the Wartburg Orphanage, around 1914 A few weeks ago I read a crushing article, “The Lost Children of Tuam,” in the New Yo...

-

George Primrose, promotional card, 1880s In my hometown of Mount Vernon, New York, Primrose Avenue ran less than a mile between two main s...

-

Montefiore Hospital's Country Home Sanitarium, early twentieth century A father and son, both stricken with tuberculosis, died 30 year...