Saturday, December 30, 2023

Thursday, November 16, 2023

Confidence Man

|

| Dr. J.W. Amey appeared in a 1918 "great men" directory. |

Ironically, the first time the newspapers took note of Jesse

Willis Amey, he was playing the role of a confidence man in a play, Black

Diamond Express.

As the 29-year old Amey toured Pennsylvania and Maryland with the

troupe Railroad Comedy Drama, he formulated grand plans for the rest of his

life. It was 1900 and he did not intend to spend much more of the twentieth

century living with his sister and brother-in-law in upstate New York.

Within a few years Amey enrolled at the New York University and Bellevue Hospital Medical College and by 1907 he was an MD ensconced in the NYU Department of Dermatology. Among his first patients, who both died, were the ringmaster of the Hippodrome Theatre and a repertory actor. The doctor always kept one foot in the theater.

Dr. Amey was living on West 45th

Street and getting around town as a member of the Friars Club and the New York

Athletic Club when he made the acquaintance of Nelle Burrelle, wealthy widow

and president of Burrelle’s Clipping Bureau.

An Ohioan named Frank Burrelle established the Bureau in New York City in 1888. Purportedly the idea came from a conversation he overheard: two businessmen in a bar bemoaning the fact that they had no way to keep track of the newspaper stories about their companies.

Frank’s second wife,

Nelle, a native of Indiana who’d led a wild life as the wife of a Pittsburgh

railroad man before she divorced him and came to New York, was creative and

enterprising. She expanded the Bureau with commemorative scrapbooks and pitched

Burrelle’s services to writers and performers on the circuit, such as Emile

Zola in 1898.

|

| Nelle and Frank embraced automobiles around the turn of the twentieth century. This article appeared in 1905. |

In 1910, Frank died unexpectedly while he and Nelle were on a cruise in the Gulf of Mexico. By that time Burrelle’s had 3,000 clients and a large office in the City Hall neighborhood where all of the New York newspapers were headquartered. Nelle moved into an apartment in the Carlton Hotel on 44th Street, which she decorated with patent medicine ads, tools, and “For Sale” signs.

On March 9, 1911, a notice

of the engagement of Nelle Burrelle to Dr J. W. Amey appeared in the society

pages. The Brooklyn Times-Union commented:

Beside having shown herself a competent

business woman and having registered the biggest year’s business in the life of

the firm, Mrs. Burrelle is well known in social circles and supports many

charities unostentatiously. Dr. Amey is one of the most popular physicians in

the city and he and Mrs. Burrelle have long been friends.

That very night Nelle denied the engagement. Amey followed with a statement: “The story of the engagement between Mrs. Burrelle and myself, as published today, was authorized by me and issued in good faith.”

Nelle mused to a reporter:

Why did Dr. Amey make such an announcement?

I suppose, in his case, the wish was father to the thought. Perhaps the doctor

has imagination and wished to carry me by storm. Well, we are not living in

medieval times. Men don’t strap their women across their horses now and carry

them away.

|

| During these years, Nelle and her company were on top of the world. |

Ten months later, Nelle fell ill at her apartment. Her death followed a 48-hour coma. Acute nephritis and uremia were listed as the causes, but the coroner received an anonymous telephone tip that hinted at murder.

Coroner Holtzhauser did not say, “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark,” but he did make an announcement: “From what I have learned thus far I believe there may be something wrong.” He performed an autopsy and ruled Nelle’s death to be of undetermined cause.

Speaking to the press, Holtzhauser expressed surprise that Dr. Amey had been one of the three physicians who attended Nelle, that Amey had put his own nurse in charge of the patient, and that he had prescribed medicine that was found at Nelle’s bedside.

The drama continued.

Dr. Amey, whose inappropriate behavior did not seem to draw further suspicion among the authorities, reported to the police that thousands of dollars’ worth of jewelry was missing from Nelle’s bedroom and her safe in the Carlton Hotel. He described two solitaire rings, a pear brooch, a purse studded with diamonds, and so on.

Nelle’s will was missing, too! But about six months later, Dr. Amey delivered Nelle’s will to the surrogate. It had been slipped under his door, he said.

Someone leaked the contents to the press. Nelle had left shares of Burrelle’s stock and money to various employees, her two sisters, and Frank Burrelle’s two children by his first wife. She named Jesse W. Amey co-executor and left him the rest of her estate.

The date of execution and Nelle’s signature were missing, rendering it invalid. Eventually Nelle’s two sisters claimed the inheritance.

Dr. Amey went on with his life, purchasing a yacht, competing in trapshooting contests, and marrying Grace May Hoffman, a coloratura soprano who toured with John Philip Sousa. The couple had two sons who were young when their mother died in 1924.

Grace’s parents were devastated—not only by their daughter’s early death. For some reason, the prospect of Dr. Amey continuing to play a part in the lives of their grandsons was out of the question.

Jesse, Jr. and Frank were reared in Manhattan until their grandfather’s death and then in Schenectady by their great-aunt Grace.

Dr. Amey never missed a chance to get his name in the papers. In the late twenties, he started a cosmetic surgery clinic well before such doctors knew what they were doing in the operating room. Mehmet Oz-like, he promoted a controversial anti-cancer serum. His pronouncements were clunky and pompous at the same time.

He fit neatly into his

time as an actor-doctor.

*Eventually Dr. Amey

wended his way to Coral Gables, Florida, remarried to a wealthy divorcee, and died

in 1939.

Tuesday, November 14, 2023

Calling Joseph Mandelkern

“Famous for his artistic eye,” the early-twentieth century theater agent Joseph Mandelkern liked to boast that he discovered the ethereal prima ballerina Anna Pavlova.

This was not true. However, between 1900 and 1924, the New York-based impresario sailed to Europe dozens of times and always returned clutching a bunch of contracts for Russian performers to tour the United States.

Perpetually wielding a cigar, Mandelkern was “Mephistophelian,” “fast-talking,” and “wily,” according to reports.* I bet that his rivals, and perhaps some of his friends, occasionally felt the urge to punch him or sue him. He landed in court at least a few times.

Yet he did help to ignite

the American passion for classical Russian ballet. In the fall of 1911, many

U.S. newspapers ran this story:

RUSSIA

FORBIDS IMPERIAL DANCERS TO LEAVE COUNTRY

The ranks of the imperial artists have been

so depleted that Chief Director Krupensky is at his wit’s end to provide a

suitable ballet to be given before the Tzar at Krasnoye Selo, the famous “red

village” near St. Petersburg where Russia’s ruler spends the summer.

At the center of the controversy stood Lydia Lopokova, one of Mandelkern’s prize catches. Beautiful and independent, Lydia possessed an extraordinary presence although she was only sixteen years old.

Three dancers—Lydia, her brother Feodor, and Alexander Volinine—signed with Mandelkern in Paris during the summer of 1910. At the time, Lydia and Alexander were performing with the avant-garde Ballets Russes.

Then Lydia disappeared. After

a few days, during which detectives dashed madly around Paris, she emerged on

the arm of a nobleman of Polish descent. He had been following her around for

months and finally persuaded her to marry him. Now they would return to Russia

for the wedding.

Mandelkern must have twisted her arm hard because Lydia changed her mind and boarded the ship. When they arrived at Ellis Island a few weeks later, she said, “I like New York very much.”

During the next two years, Lydia earned a lot of money and fame. Mandelkern booked her all over the country, including Buffalo, N.Y., where a producer arbitrarily cut Lydia’s appearances in half.

Irate, Mandelkern lost control and shouted at the audience from a private box. The police arrested him and led him from the theater. The producer followed, delivering a few body blows along the way.

After paying a $25 fine, Mandelkern was released on $300 bail. Lydia returned to Europe, married the economist John Maynard Keynes, and left Joseph Mandelkern behind.

|

| "House in the Pines," located in Jamesburg, N.J., was owned by a Russian couple. Mandelkern often visited there during the 1920s. |

After World War I, the business of artist representation saw considerable change, and there may have been less room for Joseph Mandelkern. Besides, he wanted a different life back in the old world.

In 1922 he applied for a

new passport. In his photograph, Mandelkern appears wizened, half-hidden by

large glasses and a straw boater. Six months after the passport was issued,

Mandelkern wrote to the Department of State to request that the headshot be

swapped for another picture in which he looked much younger.

|

| Passport photo, Joseph Mandelkern, 1922 |

Then he went off to Wiesbaden, where he married Therese Jung, a woman nearly 30 years younger than he. In June 1925, they moved to Merano, Italy, just south of the German border.

In May of 1938, Hitler visited Italy for the second time and enjoyed, in the words of historian Paul Baza, “a massive display of fascist spectacle in three cities: Rome, Naples and Florence.”

Soon after, Mussolini ordered the enforcement of severe antisemitic laws. Unsurprisingly, Therese and Joseph Mandelkern were marked “di razza ebraica” on a census of Jews conducted in Italy in August 1938.

|

| Hitler and Mussolini, 1938 |

There is evidence that Joseph tried unsuccessfully to return to the U.S. He suffered a stroke in December 1939, died soon after, and is buried in Merano’s Jewish Cemetery. In the official report of his death, no known relatives were listed besides Therese.

Few acknowledge that Joseph Mandelkern played a major part in shaping the cultural tastes of Americans at the turn of the twentieth century.

Really, he must have

been insufferable.

*Quotes from Bloomsbury Ballerina by Judith Mackrell, an excellent biography of Lydia Lopokova.

**https://www.jamesburg.net/jhistory.html

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2023/11/calling-joseph-mandelkern.html

Saturday, October 21, 2023

Wednesday, October 4, 2023

Joseph Mandelkern's Return to Russia

|

| Tolstoy and Gorky, 1900 |

On July 4, 1905, the Polish-born

impresario and real estate man Joseph Mandelkern landed on page two of the New

York Times.

The 41-year old hotshot had arrived in Europe a few weeks earlier. He toured Warsaw, Lodz, and Bialystok. In the small town of Dzialoszyce with its majestic synagogue, Mandelkern visited his widowed mother, whom he had not seen since 1884 when he immigrated to America.

FOUND

ANARCHY IN POLAND

JOSEPH

MANDELKERN OF NEW YORK

TELLS

OF HIS OBSERVATIONS

He saw a parade of 20,000 people carrying red flags. Revolutionaries in blue shirts. Everyone armed with pistols and knives.

It is intriguing that Mandelkern chose the summer of 1905, a scant six months after the First Russian Revolution, to make a three-month trip into political and social chaos.

Days before Mandelkern arrived in St. Petersburg, the officers of the battleship Potemkin had been overcome by revolution-minded mutineers who were enraged by their treatment during the Russo-Japanese War.

As famously portrayed in

the 1925 film Battleship Potemkin, Cossacks murdered 1,000 men, women,

and children who stood cheering the mutineers from the Richelieu Steps in

Odessa while the ship was anchored offshore in the Black Sea.

|

| Famous scene from Battleship Potemkin, directed by Soviet film director Sergei Eisenstein |

It was a dangerous, bloody

time but Mandelkern felt confident about navigating through the Russian Empire

because he possessed a “release from allegiance” signed by a consul general

named Count Ladyzhensky. Mandelkern had paid 800 rubles for the document.

A supply of Havana cigars also greased the wheels.

Crossing the border

between Germany and Russia, Mandelkern became aware of a new word, “Uligani,” derived

from the English word “hoodlum.”

It entered into every conversation he held, with friends or

strangers, in his home city. He heard it uttered in terror at the bier of a

murdered friend. When he looked for his dead father’s gravestone, the same word

was whispered into his ear by the gravedigger as a warning. When he wanted to

seek rest and recreation in a public park he heard it again on the lips of a

gendarme.

The Uligani preyed on everyone.

Now here was Mandelkern, a Jew, making his way through Russia as if he were an old friend of Nicholas and Alexandra. He also visited two anti-Czarists, famous writers both—Leo Tolstoy and Maxim Gorky.

Then Mandelkern went off to Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy’s country estate a few hours by train from Moscow. After lunch, Mandelkern learned that the Okhrana—the Czar’s secret police—regularly harassed Tolstoy. Meanwhile, the Bolsheviks demanded that he relinquish his property to divide among peasants.

Returning to the U.S. in August, Mandelkern met with a Times reporter to share grim tales of corruption, deprivation, and violence.

Nonetheless, Mandelkern told the reporter, he detected courage among the Russians, a willingness to speak out against the Czar’s tyranny and the waste of the Russo-Japanese War.

***

By the time of his 1905 visit, Mandelkern had established himself as a stealthy theater agent who nabbed gifted performers. His fluency in English, Russian, and Polish enabled him to execute contracts before anyone else in the room knew the details.

Always in motion, Mandelkern traveled through the Midwest and to Europe. His wife Pauline and their five children—at least two of whom were already superb musicians—watched him come and go.

One senses he was aloof and finicky.

He certainly had no time for his family in 1906, when Maxim Gorky accepted an invitation to come to America. Mandelkern even hinted at the possibility of a visit with President Theodore Roosevelt.

On a sparkly April day, Gorky arrived at Hoboken on a German steamship. A crowd of 1,000 greeted him. At the end of the gangplank, a delegation of socialists stretched out its hands: Abraham Cahan, editor of The Forward; Morris Hillquit, a labor lawyer; Gaylord Wilshire, a California entrepreneur; Leroy Scott, a writer and settlement worker; and Joseph Mandelkern.

Thus began Gorky’s high-flying adventure with Mandelkern at his elbow. Lunch at the St. Regis. A visit to Grant’s Tomb. Watching children feed the squirrels in Central Park. The circus at Madison Square Garden.

“In a Russian city almost every other man one meets is either a soldier or a policeman,” Gorky told Mandelkern. “I haven’t seen a single soldier all day, and only two policemen. Marvelous!”

That evening, he was driven down Fifth Avenue to “Club A,” a brownstone owned by a group of revolutionary-minded New Yorkers. Here would occur the highlight of Gorky’s visit: dinner with Mark Twain, William Dean Howells, and other American writers who supported the movement to overthrow the Czar.

A few days later, however, Gorky was beset by scandal.

It turned out that the writer had left his wife Katharine and two sons back in Russia. The woman who accompanied him to the U.S. was actress Maria Feodorovna Andreyeva, his mistress of several years.

Now Gorky ran into an American

problem: relentless prudishness about an issue that would have been irrelevant

in Russia.

|

| Hotel Brevoort, Fifth Avenue & Eighth Street |

Tossed from the Hotel Rhinelander to the Hotel Brevoort to the Hotel Belleclaire, denounced by the press and pushed away ever so gently by Twain et al, Gorky and Andreyeva found themselves begging for a place to lay their heads.

Joseph Mandelkern, who was very enthusiastic at first in his

eulogies of Gorky, said to a reporter for the Eagle that he had known it

for a long time and that others on this side knew of the relations with the

actress.

It does not appear that Gorky and Andreyeva went back uptown to stay with the Mandelkern family.

To be continued.

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2023/10/joseph-mandelkerns-return-to-russia.html

Wednesday, September 6, 2023

Interrogating Joseph Mandelkern

In 1886, Joseph Mandelkern left his desk job in Bialystok City Hall and immigrated to America. His plans were far grander than many an Eastern European newcomer. He already knew that he would become an impresario.

After settling in New York City, Mandelkern placed a newspaper announcement that he had established a “New Yiddish Theatre.” Then he sailed off to London to recruit famous Yiddish-speaking performers. He had his eye on Jacob P. Adler, once a juvenile delinquent; now a renowned European actor.*

Wackily, the trip was funded by two wealthy Chicago clothiers named Rosengarten and Drozdovitch who thought that New York had no business staking a claim on Yiddish theater.

But the deal fell apart and Mandelkern came home instead with the team of Moishe Finkel and Sigmund Mogulesko, who had been a smash hit on the Romanian stage.

It didn’t bother Mandelkern that they were not a hit in New York. He had bigger fish to fry.

In 1889, Mandelkern traveled to Russia, Rumania, and Austria in search of more performers. Until the early 1920s, he would visit Russia recurrently through pogroms, war, and revolution.

Most Jews who fled Eastern Europe in the late nineteenth century did not intend to return to the land of persecution. Joseph Mandelkern’s ambition left no room for fear. Armed with a document which took two years to obtain, he managed to dodge reprisals—to put it mildly—from Cossacks and “Uligani,” as hoodlums were known.

In June 1910, the Brooklyn

Daily Eagle reported:

It appeared yesterday that while Oscar Hammerstein, the

impresario, had been barred out of Russia, it is said, because of his Jewish

parentage, and also because it had become known that he was seeking to persuade

Russian singers and dancers, favorites of the Czar, to leave Russia, Joseph

Mandelkern, another Jewish impresario of this city, had been freely traveling

through the Czar’s domains. Mr. Mandelkern, who lives at 20 East 120th

Street in this city, just received in Moscow and St. Petersburg, had great

success in contracting with popular ballet and operatic favorites of both

cities for American tours.

Evidently Mandelkern liked

to show off, tempt fate, and challenge authority.

That is why I wish the brilliant, effervescent dance critic Ann Barzel were still alive to explain Mandelkern to me. I met Ann in the summer of 1982 when she spent two weeks in Jackson, Mississippi covering the International Ballet Competition for Dance Magazine and Dance News.

At 77 years old, she had been devoted to all aspects of dance since the age of fourteen although she didn’t care for “Twyla Twerp.”

Since I was the Competition’s director of public relations, Ann and I spoke often even before the competition. In particular, she shared insight and background on the esteemed jury co-chaired by Robert Joffrey.

|

| Ann Barzel contributed an essay to the program for the 1982 International Ballet Competition. |

A few days after the appointment, Miss Golovkina called me to ask about proper attire for the galas to which she had been invited.

“I plan to wear the silk pajama,” she confided.

Ann loved the story.

Born in 1915, Sofia Golovkina would have been too young for Joseph Mandelkern to pluck from the arms of Mother Russia and put on tour in the United States.

But Ann—with her encyclopedic knowledge of the history of ballet and the business of dance—might have been able to explain Joseph Mandelkern’s rapid ascent as an agent and producer.

Was he a Czarist, a socialist or a capitalist? How did he manage to poach all of those Eastern European dancers and actors? And why did he leave the United States so hastily in 1924?

To be continued.

*Jacob Adler’s daughter

founded the Stella Adler School of Acting in 1949.

Monday, July 10, 2023

Wednesday, June 14, 2023

The Unexpected Journey of Mary Rankin Cranston

In New York City toward the end of the nineteenth century, Mary Rankin Cranston lodged in a boarding house on West 56th Street and worked as a librarian at the American Institute of Social Service.

Not long before she started to call herself a “social engineer” and sailed to Europe to make a study of working conditions, she had fled the South and a husband twenty years her senior whom she married when she was a belle of Atlanta.

Born in 1873, daughter of a druggist who called himself a doctor, Mamie Rankin must have had a serious reason for leaving Henry Cranston. Now known as Mary, she “came to New York with a definite and clear idea of what she wanted to do,” according to Success Magazine, which saluted her in 1905.

Cranston had never expected to earn a living but, after training as a librarian, she collaborated with two eminent reformers—Dr. Josiah Strong and Dr. W.H. Tolman—who had just established the Institute. Social betterment and eliminating urban poverty were their crusades.

|

| Dr. Josiah Strong |

Dr. Strong, a Social Gospel adherent whose chauvinistic beliefs about Anglo-Saxonism and Protestantism would be considered unacceptable today, sought solutions to alienation and destitution. Dr. Tolman, who had studied the nascent field of sociology at Johns Hopkins, focused on problems of industrialization and “fresh-air” programs like vacation schools.

It was within this Progressive agenda that Mary Rankin Cranston found a home. A librarian untypical of her time, Cranston created from scratch a “social clearing-house,” she explained to Harper’s Monthly in 1906. All available data and written material related to social improvement and urban issues were gathered in the Institute's library.

She enthusiastically loaned most of the 1,500 volumes, 5,000

pamphlets, and countless articles to social workers, municipal officials, politicians,

business people, clergy, journalists, and students worldwide.

|

| Cranston contributed articles to various publications, including "Homes of the Poor in Large Cities" in the January 1902 issue of Social Service. |

While expanding the

library, Cranston took time to pursue her own research. “The Housing of the

Negro in New York City,” which appeared in Southern Workman, in 1902,

was widely reprinted. She wrote:

If white people have found it a hard

proposition to obtain decent homes in New York, it has been even worse for the

“brother in black” who must here as everywhere else take what he can get

without any choice in the matter. Wherever the Negro has gone—North, East,

South and West—he has found the same prejudice, more or less strongly expressed

in various localities, but always the same thing at the last analysis.

Theoretically some may advocate social equality but usually with the mental

reservation that it shall be at a safe distance from its champions. It is this

prejudice which forces the colored population into almost unhabitable quarters

in our cities, large and small.

|

| Photographs that illustrated Cranston's article, "The Housing of the Negro in New York City." |

A year later, in “The New

Industrialism,” Cranston observed:

The most serious disadvantage to the workingman of the introduction of machinery lies in his danger of becoming a mere machine himself.

Cranston’s lectures and articles began to draw attention from philanthropists like Helen Miller Gould, daughter of the robber baron Jay Gould, who had inherited several of his millions in 1892 and spent much of it on social reform.

Then, suddenly, came change.

Perhaps Cranston seized the idea from the backyard and vacant-lot gardens which had sprung up as antidotes to life in the dirty, unpastoral city. Perhaps she burned out. Either way, by spring of 1910 she was ensconced in an old farm in North Brunswick, N.J.; occupation: poultry farmer.

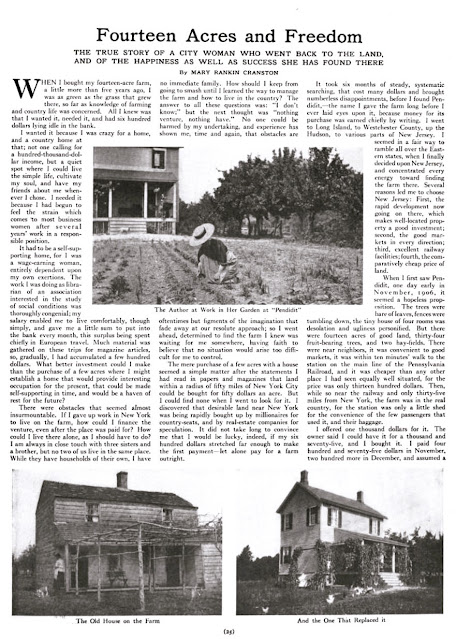

Cranston spent her savings to purchase the property, which she named “Pendidit” because writing had provided the necessary money. In 1911, Country Life in America featured her as part of its “Cutting Loose from the City” series.

HOW

ONE WOMAN, WITHOUT FAMILY OR MEANS, AND WITHOUT ANY PREVIOUS AGRICULTURAL

EXPERIENCE, HAS LAID THE FOUNDATION FOR AN OLD AGE OF PEACE AND PLENTY, AND AT

THE SAME TIME ADDED A PRESENT ZEST TO LIFE BY GETTING “BACK TO THE LAND”

|

| The first page of Cranston's article, "Fourteen Acres and Freedom" (Suburban Life, 1913) |

Cranston remained a writer and occasionally published articles about farming. And in 1916, the same year that her first husband, Henry Cranston, died in Georgia, she remarried. She and Matthew B. Thomas, a farmer, were together until her death in 1931.

One can’t help asking a few questions about Mary Rankin Cranston Thomas. Of course, many a nineteenth-century Southern belle extricated herself from society and sought education and purpose.

But there’s that twist—walking away from what seemed to be the passion of her life. Especially when she had achieved such success.

Perhaps Cranston’s change

was simple: she answered a second calling.

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2023/06/the-unexpected-journey-of-mary-rankin.html

Wednesday, April 12, 2023

Story of Henry Littlefield - Part 2

|

| Henry Littlefield's grandfather, Walter Littlefield, was an eminent journalist, editor, and author. |

The journalist Walter

Littlefield could tackle any subject.

Emile

Zola: Novelist and Reformer - 1902

Russia

in Revolution - 1905

The

Birth of United South Africa a Unique Event - 1910

Should

We Build a Channel Tunnel? - 1917

Dante

in Art and Translation - 1922

This list is the tip of

the iceberg. In beautiful economical prose, Littlefield wrote

about the American West, the charms of New England; war, European politics, the

Wahhabis’ 1924 invasion of the Hejaz . . .

Walter Littlefield was a reporter and editor at the New York Times (1898-1941), a literary correspondent for the Chicago Record-Herald (1903-1913), and the author, editor or translator of books about James Russell Lowell, Dante, Lord Byron, and Captain Alfred Dreyfus.

|

| Littlefield's best-known story about Dreyfus appeared in Munsey's Magazine in 1899. |

His coverage of the Dreyfus Affair rendered him an expert on the case and enabled him to make the leap from his native Boston to New York City in 1898. He and his elegant, Italian-born wife, Luigina Pagani Littlefield, would live in Greenwich Village until the 1940s.

Born in 1867, a descendant of English colonists, Walter began publishing his own short stories in 1889, the year he entered Harvard to study languages and history. On the side he tutored college-bound students in comparative literature, fine arts, and languages.

|

| After he graduated from Harvard, Walter Littlefield taught and tutored in Boston. |

By 1893 Walter had graduated and married Luigina, a “gifted musician with a voice of more than ordinary richness, educated at the Notre Dame Academy,” the newspapers reported.

She was the daughter of Dr. Joseph Pagani, who studied medicine in Rome and Palermo before immigrating to the U.S. in 1865. Inexplicably, Pagani received a medal from Dom Pedro II, the last monarch of Brazil, and was a member of an ancient Russian Aryan order.

Mussolini is being called a dictator. But so was Garibaldi, when he seemed to be carrying on war in defiance of the orders of King Victor Emmanuel. It is easy to mistake, in times of political turmoil, the words of a disciplinarian for those of a dictator. Like Garibaldi, Mussolini is a severe disciplinarian, but no dictator. How can he be when he swears to recognize the authority of his Majesty?

One year later, the Times

published Walter’s poem, “Fascisti.” In appreciation of the poem, Victor

Emmanuel declared Walter a Commendatore della Corona

d’Italia (Knight of the Crown of Italy) in 1933.

|

| Littlefield wrote his poem in the early 1920s. |

Between his knighting, the Reichstag fire, and other momentous events, Walter must have been unusually preoccupied in 1933 when he and Luigina became the grandparents of Henry Miller Littlefield, son of their son Henry Mario Littlefield.

Actually, Henry Miller Littlefield was the second child of Henry Mario Littlefield, who had a daughter by a previous marriage and would soon head to Reno to divorce his second wife, Elizabeth, mother of newborn Henry.

|

| Reno, 1933: "wild scenes were enacted at the office of County Clerk 'Boss' Beemer." |

Luigina died in 1945 and Walter in 1948, by which time they had left West Twelfth Street and moved, oddly, to the town of New Canaan, Connecticut. By then, Henry Miller Littlefield was a teenager.

Since he told students that he grew up without a father, one wonders whether he ever met his paternal grandparents. He grew up to become an imaginative historian and teacher of whom Walter and Luigina would have been proud (even if they disagreed about Mussolini).

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2023/04/story-of-henry-littlefield-part-2.html

Wednesday, March 8, 2023

Story of Henry Littlefield

During the 1960s when my brother and I were growing up in Mount Vernon, N.Y., our parents and their friends occasionally mentioned Henry Littlefield, who taught American history to the city’s high school students.

It was wonderful that such an imaginative young man counted among a faculty still inhabited by Victorian women who were creeping into the modern era.

In 1964, Henry Littlefield

published “The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism” in the American Quarterly.1

This article was the first to interpret L. Frank Baum’s 1900 children’s

book as a tale of politics and society in late nineteenth-century America. Nearly

30 years later, Littlefield recalled the summer of 1963:

Toward the end of July, I was reading the

opening chapters of The Wizard to my two daughters, then ages five and

two. At the same time, in the [summer school] history course I taught, we were

going through the Populist period and the 1890s. I lived just a few blocks from

the school and remember running to class the next day, to my classroom on that

hot, airless third floor.2

Excitedly, Littlefield told the students: “Guess what? In The Wizard of Oz . . . Dorothy walks on a yellow brick road . . .” He suggested that the Scarecrow was a farmer who felt stupid and the Tin Woodman a laborer dehumanized by industrialization. Dorothy and her little band, marching toward the Emerald City, represented Coxey’s Army, and the Wizard could be any president, really, but likely William McKinley.

|

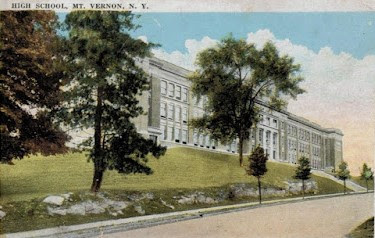

| A. B. Davis High School, around 1915 |

The students were enthused but the article languished until 1977, when Gore Vidal wrote about it in the New York Review of Books. By that time, Littlefield had earned his PhD at Columbia University and moved on to Amherst College and then California where he taught at Golden Gate University and the Naval Postgraduate School.

By the mid-1980s, Littlefield’s thesis about Oz and populism had developed its own academic niche. Some of its proponents scrutinized Oz as an allegory in which each word, each moment, was loaded with symbolism.

And they were self-righteous to boot, in the opinion of Michael Gessel, then editor of the Baum Bugle. Like Littlefield, he regarded the book as a parable on populism that happened to serve as an excellent teaching tool. Both men dismissed “outlandish” interpretations.3

Born in Manhattan in 1933, Littlefield grew up without a father, he once confided to a student.4 But he does not seem to have discussed his family, which was full of intrigue and achievement.

Around 1935, Henry’s mother, Elizabeth Miller Littlefield, divorced his father, Henry Mario Littlefield, in Reno. As was often the case in these sticky situations, Elizabeth’s parents invited their daughter and grandson to move into their brownstone on West 148th Street.

Jesse Preston Miller, known as Dr. J. Preston Miller, ruled the household. The son of a Greenville, S.C. grocer, Miller had made his way north around 1900, married, and established a successful medical practice.

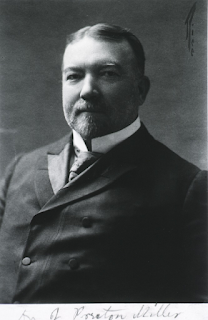

|

| J. Preston Miller, M.D. |

Henry's father may have disappeared, but the boy's paternal grandparents lived on West Twelfth Street in Greenwich Village. It cannot be known whether he ever trekked downtown to visit them. What a time that would have been!

In 1940, Walter

Littlefield was at the peak of his influence as foreign editor of the New

York Times although his wife Luigina’s fabulous Manhattan salon had wound down in

the late twenties . . .

|

| Walter Littlefield |

To be continued.

1 Henry M. Littlefield, “The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism,” American Quarterly, Spring 1964, 47-58.

2 Henry M. Littlefield, “The Wizard of Allegory,” The Baum Bugle, Spring 1992, 24-25.

3 Michael Gessel, “Tale of a Parable,” The Baum Bugle, Spring 1992, 19-23.

4 Richard J. Garfunkel, https://www.richardjgarfunkel.com/2015/01/29/656/

*The Baum Bugle, founded in 1957, is the official journal of the International Wizard of Oz Club: https://www.ozclub.org/publications/the-baum-bugle/

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2023/03/the-tale-of-henry-littlefield.html

Conjuring Jane Pierce

Imagine Jane Pierce in her black gown and mantilla. She sits on a slipper rocker in her second-floor bedroom in the White House. Clutching...

-

Postcard of the Wartburg Orphanage, around 1914 A few weeks ago I read a crushing article, “The Lost Children of Tuam,” in the New Yo...

-

George Primrose, promotional card, 1880s In my hometown of Mount Vernon, New York, Primrose Avenue ran less than a mile between two main s...

-

Montefiore Hospital's Country Home Sanitarium, early twentieth century A father and son, both stricken with tuberculosis, died 30 year...