During the 1960s when my brother and I were growing up in Mount Vernon, N.Y., our parents and their friends occasionally mentioned Henry Littlefield, who taught American history to the city’s high school students.

It was wonderful that such an imaginative young man counted among a faculty still inhabited by Victorian women who were creeping into the modern era.

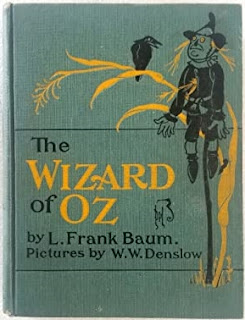

In 1964, Henry Littlefield

published “The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism” in the American Quarterly.1

This article was the first to interpret L. Frank Baum’s 1900 children’s

book as a tale of politics and society in late nineteenth-century America. Nearly

30 years later, Littlefield recalled the summer of 1963:

Toward the end of July, I was reading the

opening chapters of The Wizard to my two daughters, then ages five and

two. At the same time, in the [summer school] history course I taught, we were

going through the Populist period and the 1890s. I lived just a few blocks from

the school and remember running to class the next day, to my classroom on that

hot, airless third floor.2

Excitedly, Littlefield told the students: “Guess what? In The Wizard of Oz . . . Dorothy walks on a yellow brick road . . .” He suggested that the Scarecrow was a farmer who felt stupid and the Tin Woodman a laborer dehumanized by industrialization. Dorothy and her little band, marching toward the Emerald City, represented Coxey’s Army, and the Wizard could be any president, really, but likely William McKinley.

|

| A. B. Davis High School, around 1915 |

The students were enthused but the article languished until 1977, when Gore Vidal wrote about it in the New York Review of Books. By that time, Littlefield had earned his PhD at Columbia University and moved on to Amherst College and then California where he taught at Golden Gate University and the Naval Postgraduate School.

By the mid-1980s, Littlefield’s thesis about Oz and populism had developed its own academic niche. Some of its proponents scrutinized Oz as an allegory in which each word, each moment, was loaded with symbolism.

And they were self-righteous to boot, in the opinion of Michael Gessel, then editor of the Baum Bugle. Like Littlefield, he regarded the book as a parable on populism that happened to serve as an excellent teaching tool. Both men dismissed “outlandish” interpretations.3

Born in Manhattan in 1933, Littlefield grew up without a father, he once confided to a student.4 But he does not seem to have discussed his family, which was full of intrigue and achievement.

Around 1935, Henry’s mother, Elizabeth Miller Littlefield, divorced his father, Henry Mario Littlefield, in Reno. As was often the case in these sticky situations, Elizabeth’s parents invited their daughter and grandson to move into their brownstone on West 148th Street.

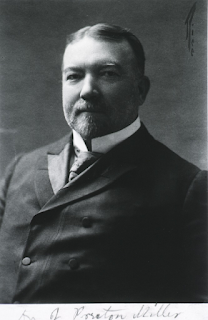

Jesse Preston Miller, known as Dr. J. Preston Miller, ruled the household. The son of a Greenville, S.C. grocer, Miller had made his way north around 1900, married, and established a successful medical practice.

|

| J. Preston Miller, M.D. |

Henry's father may have disappeared, but the boy's paternal grandparents lived on West Twelfth Street in Greenwich Village. It cannot be known whether he ever trekked downtown to visit them. What a time that would have been!

In 1940, Walter

Littlefield was at the peak of his influence as foreign editor of the New

York Times although his wife Luigina’s fabulous Manhattan salon had wound down in

the late twenties . . .

|

| Walter Littlefield |

To be continued.

1 Henry M. Littlefield, “The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism,” American Quarterly, Spring 1964, 47-58.

2 Henry M. Littlefield, “The Wizard of Allegory,” The Baum Bugle, Spring 1992, 24-25.

3 Michael Gessel, “Tale of a Parable,” The Baum Bugle, Spring 1992, 19-23.

4 Richard J. Garfunkel, https://www.richardjgarfunkel.com/2015/01/29/656/

*The Baum Bugle, founded in 1957, is the official journal of the International Wizard of Oz Club: https://www.ozclub.org/publications/the-baum-bugle/

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2023/03/the-tale-of-henry-littlefield.html