|

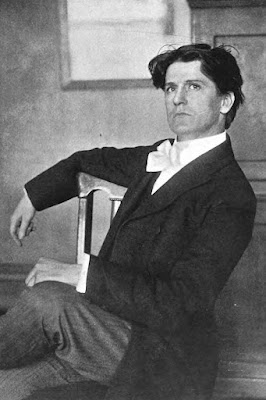

| Charles Hemstreet, 1900s |

Up in Buffalo, N.Y., Lake Erie narrows like a funnel into the Niagara River. Even before the Erie Canal opened in 1825 and through the nineteenth century, a shipbuilding industry flourished on the American side of the river.

Charles Hemstreet’s father, William, was a Buffalo ship carpenter who helped build some of the steamers that plied Lake Erie carrying freight and passengers. William’s oldest son, Felix, became a ship carpenter’s apprentice at the age of fourteen.

But Charles, born in 1866, had greater aspirations. Although he advanced no farther in school than sixth grade, Charles loved to read newspapers and books about history. Around 1885, he went south to New York City to look for a job that would suit his interests.

During these years, the

city was home to at least fifteen daily English language newspapers. Charles worked

as a police reporter at a time when the department was at its most corrupt. The

job required much hanging around headquarters on Mulberry Street. Charles

stayed a few years, then became night manager of the Associated Press, a

position he held for a decade.

|

| New York City Police Headquarters, 1890s when Theodore Roosevelt was Commissioner |

Everything seemed to come his way, this foppish young man with a poet’s hair, dark and wavy, who liked to assume dramatic poses.

An officer of the New York

Press Club, Charles often visited a shaky old building on Spruce Street, off

Newspaper Row near City Hall Park, to carouse with fellow members of the

notorious Blue Pencil Club.

|

| Blue Pencil Club members at play |

He’d bound up and down the stairs with a bunch of mischievous, irreverent reporters, editors, writers, cartoonists, and illustrators. They published a bawdy short-lived magazine and ran all over town drinking and declaiming.

Charles’s wife, Marie Meinell, daughter of a grumpy Civil War veteran from Oyster Bay, also joined the Blue Pencil Club. Not only did Marie qualify as a published author (of insipid poetry), but she was mischievous, too.

In 1893, quarantined in a hospital with scarlet fever, Marie decided to escape by sliding down a rope to the street. Traveling under the name “Edith Fish” because she thought she might be sent to prison for running away, Marie raced off to Jersey City and Philadelphia. Finally she made her way to the Adirondacks where Charles came to comfort her and presumably did not catch scarlet fever.

Charles was just 34 when he announced his retirement from journalism. According to a widely published notice, he would now devote himself to writing books. His first one, Nooks & Corners of Old New York, was published by Scribner’s in 1899, followed by The Story of Manhattan (1901), When Old New York was Young (1902), and Literary New York (1903).

But Charles couldn’t just

sit around and write books. One day he was called to the scene of an excavation

for the subway in lower Manhattan. Italian immigrant laborers had unearthed a

stone from a Revolutionary War fort. He told a Times reporter:

I understand that the contractor is

preparing to present the slab to the New-York Historical Society. I will do all

I can to prevent this. Once in the possession of the society it would be as

inaccessible to the general public as though it had been left in its

underground resting place.

He was correct. And how delightful to be regarded as an expert on old New York, long the domain of patricians with trailing pedigrees.

In 1906, Charles and Marie sailed to Europe to collaborate with Jeannette Pomeroy on a scientific study of the appearance of American women. Mrs. Pomeroy, an English woman descended from Indian occultists—she said—was widely admired for her beauty advice and business acumen. The New-York Tribune reported:

If Mrs. Pomeroy is right in her conclusions

that the women of America are growing less beautiful year by year, she will

invoke national, state and municipal governments to aid her in forcing women to

become beautiful whether they will or not.

The remedy for the dearth

of beautiful women, Charles said in a statement, “is to simply surround women

with delectable odors, dulcet sounds, palatable foods, beautiful sights, and

correct ideas.”

|

| Mrs. Jeannette Pomeroy |

I was sorry to learn that

Charles dealt in such sexist foolishness because he’s so likable otherwise.

Enmeshed in a lawsuit that would result in the loss of her cosmetics empire, Mrs. Pomeroy faded from the scene while Charles and Marie stuck around to research a book, Nooks and Corners of Old London. Once back in the U.S., Charles accepted the position of manager of Burrelle’s Press Clipping Bureau. He had found a new career.

Nelle Burrelle deserves her own novel. It suffices to say she was an adventuress. When Louis Chevrolet invited her to race with him, they circled the 1-1/2 mile Morris Park Racetrack in 53 seconds. Shortly before her own mysterious death, she flew around in a Curtiss airplane above Mineola Field on Long Island.

|

| Nelle Burrelle, 1910 |

In 1911 Nelle fell ill at

her apartment in the Carlton Hotel on 44th Street and was attended

for several days by three physicians, including Dr. Jesse W. Amey whose

romantic advances she had spurned after her husband’s death. The physicians

listed acute nephritis as the cause of death but the coroner received an

anonymous tip that Nelle had been murdered. He performed an autopsy and ruled

her death to be of undetermined cause.

|

| Burrelle's advertisement, about 1915 |

The date and Nelle’s signature

were missing, rendering the will invalid. Unsurprisingly, given the shady

story, someone leaked its contents: 16 shares of Burrelle Clipping Bureau stock

to Charles Hemstreet, $2,000 to Marie Hemstreet, a few shares to various

employees and relatives, and the balance to Dr. Jesse W. Amey.

One year later, the same surrogate approved a different will for probate. It split the estate between Nelle’s two sisters. And that was that.

If Charles Hemstreet was left out in the cold, he carried on at Burrelle’s and drew income from his books, which continued to be popular with the exception of a novel, The Don Quixote of America, the Story of an Idea, published in 1921.

The book stars John Eagle of upstate New York, who dreams of building a new city in the western wilderness and travels by train to Los Angeles. There, nothing goes his way. He is beaten up and the butt of jokes. Upon his return home, however, he is greeted with fanfare and hailed by his friends and family.

One critic wrote:

The jacket hints of an “underlying idea.” I

have spent weary nights over the home brew trying to excavate it. I leave it

for future literary archeologists to unearth.

Charles Hemstreet of America, an idea for a story.

*Charles Hemstreet died in

1941 and Marie in 1943.

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2022/10/chasing-charles-hemstreet.html