|

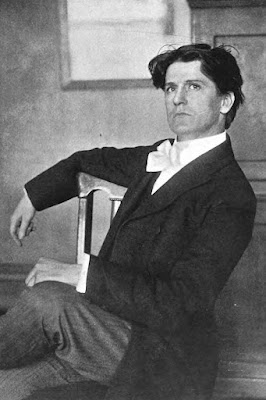

| Dr. J.W. Amey appeared in a 1918 "great men" directory. |

Ironically, the first time the newspapers took note of Jesse

Willis Amey, he was playing the role of a confidence man in a play, Black

Diamond Express.

As the 29-year old Amey toured Pennsylvania and Maryland with the

troupe Railroad Comedy Drama, he formulated grand plans for the rest of his

life. It was 1900 and he did not intend to spend much more of the twentieth

century living with his sister and brother-in-law in upstate New York.

Within a few years Amey enrolled at the New York University and Bellevue Hospital Medical College and by 1907 he was an MD ensconced in the NYU Department of Dermatology. Among his first patients, who both died, were the ringmaster of the Hippodrome Theatre and a repertory actor. The doctor always kept one foot in the theater.

Dr. Amey was living on West 45th

Street and getting around town as a member of the Friars Club and the New York

Athletic Club when he made the acquaintance of Nelle Burrelle, wealthy widow

and president of Burrelle’s Clipping Bureau.

An Ohioan named Frank Burrelle established the Bureau in New York City in 1888. Purportedly the idea came from a conversation he overheard: two businessmen in a bar bemoaning the fact that they had no way to keep track of the newspaper stories about their companies.

Frank’s second wife,

Nelle, a native of Indiana who’d led a wild life as the wife of a Pittsburgh

railroad man before she divorced him and came to New York, was creative and

enterprising. She expanded the Bureau with commemorative scrapbooks and pitched

Burrelle’s services to writers and performers on the circuit, such as Emile

Zola in 1898.

|

| Nelle and Frank embraced automobiles around the turn of the twentieth century. This article appeared in 1905. |

In 1910, Frank died unexpectedly while he and Nelle were on a cruise in the Gulf of Mexico. By that time Burrelle’s had 3,000 clients and a large office in the City Hall neighborhood where all of the New York newspapers were headquartered. Nelle moved into an apartment in the Carlton Hotel on 44th Street, which she decorated with patent medicine ads, tools, and “For Sale” signs.

On March 9, 1911, a notice

of the engagement of Nelle Burrelle to Dr J. W. Amey appeared in the society

pages. The Brooklyn Times-Union commented:

Beside having shown herself a competent

business woman and having registered the biggest year’s business in the life of

the firm, Mrs. Burrelle is well known in social circles and supports many

charities unostentatiously. Dr. Amey is one of the most popular physicians in

the city and he and Mrs. Burrelle have long been friends.

That very night Nelle denied the engagement. Amey followed with a statement: “The story of the engagement between Mrs. Burrelle and myself, as published today, was authorized by me and issued in good faith.”

Nelle mused to a reporter:

Why did Dr. Amey make such an announcement?

I suppose, in his case, the wish was father to the thought. Perhaps the doctor

has imagination and wished to carry me by storm. Well, we are not living in

medieval times. Men don’t strap their women across their horses now and carry

them away.

|

| During these years, Nelle and her company were on top of the world. |

Ten months later, Nelle fell ill at her apartment. Her death followed a 48-hour coma. Acute nephritis and uremia were listed as the causes, but the coroner received an anonymous telephone tip that hinted at murder.

Coroner Holtzhauser did not say, “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark,” but he did make an announcement: “From what I have learned thus far I believe there may be something wrong.” He performed an autopsy and ruled Nelle’s death to be of undetermined cause.

Speaking to the press, Holtzhauser expressed surprise that Dr. Amey had been one of the three physicians who attended Nelle, that Amey had put his own nurse in charge of the patient, and that he had prescribed medicine that was found at Nelle’s bedside.

The drama continued.

Dr. Amey, whose inappropriate behavior did not seem to draw further suspicion among the authorities, reported to the police that thousands of dollars’ worth of jewelry was missing from Nelle’s bedroom and her safe in the Carlton Hotel. He described two solitaire rings, a pear brooch, a purse studded with diamonds, and so on.

Nelle’s will was missing, too! But about six months later, Dr. Amey delivered Nelle’s will to the surrogate. It had been slipped under his door, he said.

Someone leaked the contents to the press. Nelle had left shares of Burrelle’s stock and money to various employees, her two sisters, and Frank Burrelle’s two children by his first wife. She named Jesse W. Amey co-executor and left him the rest of her estate.

The date of execution and Nelle’s signature were missing, rendering it invalid. Eventually Nelle’s two sisters claimed the inheritance.

Dr. Amey went on with his life, purchasing a yacht, competing in trapshooting contests, and marrying Grace May Hoffman, a coloratura soprano who toured with John Philip Sousa. The couple had two sons who were young when their mother died in 1924.

Grace’s parents were devastated—not only by their daughter’s early death. For some reason, the prospect of Dr. Amey continuing to play a part in the lives of their grandsons was out of the question.

Jesse, Jr. and Frank were reared in Manhattan until their grandfather’s death and then in Schenectady by their great-aunt Grace.

Dr. Amey never missed a chance to get his name in the papers. In the late twenties, he started a cosmetic surgery clinic well before such doctors knew what they were doing in the operating room. Mehmet Oz-like, he promoted a controversial anti-cancer serum. His pronouncements were clunky and pompous at the same time.

He fit neatly into his

time as an actor-doctor.

*Eventually Dr. Amey

wended his way to Coral Gables, Florida, remarried to a wealthy divorcee, and died

in 1939.