|

| Business card of Carlisle Kawbawgam |

In 1912 the Red Caruso

burst on the scene, drawing admiration and sneers from both sides of the

Atlantic.

Six feet tall, the papers reported, and a magnificent tenor, twenty-six year old Carlisle Kawbawgam told the world that he was the son of the last chief of the Chippewa tribe of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

“The copper-colored Indian is a magnificent specimen of young manhood,” declared the New York Dramatic Mirror. Audiences and critics predicted that Kawbawgam would soar. He had a brilliant future in opera, they said.

At least one editor spewed venom:

The spectacle of Poor Lo singing high “C” should be sufficient

to give one pause. Incidentally, if there is any foundation in fact for the

story, we would advise “Jim” Thorpe to get out of his present popularity all

that he can.

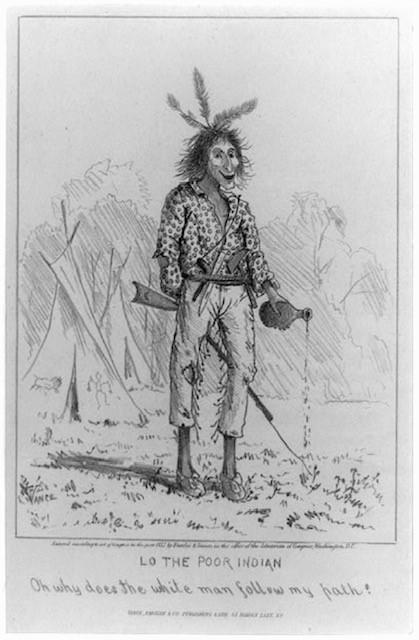

“Poor Lo,” a derogatory name for Native Americans, became popular in the U.S. during the nineteenth century. It derives from “An Essay on Man” by the English poet Alexander Pope, who wrote:

Lo, the poor Indian! whose untutored mind

Sees God in clouds, or hears Him in the wind . . .

|

| "LO THE POOR INDIAN" (1875) (Library of Congress) |

The Upper Peninsula is perched above the mitten of Michigan, surrounded by the lakes Huron, Michigan, and Superior. There, Carlisle Kawbawgam was born in 1882. However, the chief whom he claimed as his father had no children. More than a few puzzling facts or fibs would follow.

During adolescence, Kawbawgam said, he left the Chippewa village and traveled to Pennsylvania to enroll at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. If he actually attended Carlisle, he may have entered willingly or forcibly. The government-run boarding school had one goal: total assimilation and acculturation in white society. Students were brutally subjected to reprogramming.

Later, when he became a singer, Kawbawgam announced that he chose the name “Carlisle” as a tribute to his alma mater. Immediately, numerous journalists and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs wrote to Moses Friedman, superintendent of the school, inquiring about the former student. Friedman replied that he had no record of this famous alumnus.

|

| Carlisle School Superintendent Moses Friedman informs the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs that Carlisle Kawbawgam never attended the boarding school. |

Now the young man, it would be reported, went off to the Yale School of Medicine—except Yale has no record of his enrollment. The

first Native American graduate of Yale, Henry Roe Cloud, received a B.A. in

1910.

Kawbawgam may have attended Yale under a different name. But in the age of Jim Crow, it is unlikely that a Native American—even "unblanketed and unmoccasined," as one observer noted—could have passed.

Onward to Washington, D.C., where Theodore Roosevelt inhabited the presidency and smart society had sprung back to life after years of late Victorian stuffiness.

There, Kawbawgam practiced medicine and sang at private events to earn extra money. During a performance for a Latin American legation, he met and fell in love with Alma Lopez, a Chilean woman of Aztec descent. They married and sailed to Europe. Kawbawgam planned to tour, then settle in Berlin to study with an American expat, Frank King Clark, a well-known voice and elocution teacher.

|

| Advertisement for one of Kawbawgam's performances in Berlin |

In December 1912, rave

reviews started flying across the ocean.

GERMANS

DISCOVER AN INDIAN CARUSO

Graduate

of Carlisle School

Hailed

in Berlin and Vienna

As

Coming Opera Star

TO

GIVE UP VAUDEVILLE

But Kawbawgam did not give

up vaudeville. He continued to perform in music halls, never opera houses. Perhaps

he studied with Clark until war broke out in 1914; then he and his wife moved

to London. There he appeared regularly, always with second billing, at the Trocadero

Restaurant and the Alhambra.

Often appearing alongside him were an Australian swimmer and

diver, Annette Kellermann; a Parisian torch singer, Mlle. Damia; and a Japanese family

of ventriloquists and pantomimists, the Hammamuras.

Of Kawbawgam, English critics “declared unreservedly that an undeniably wonderful talent lies hidden in his bronze throat,” according to a report in the New York Times.

He lately inherited the chieftaincy of the Chippewa through

the death of his father, is erect as a sycamore and Indian in every line of his

gaunt frame and physiognomy. He is really a “medicine man” by profession. . .

While Kawbawgam performed as a singer in the London variety shows, he probably also had parts in minstrel-type skits like “The Indian Mail Carrier” and “Queen of the Redskins.”

He and Alma stayed in England through World War I. Carlisle Jr. was born in 1916 and little Alma came along in 1919. A few years later, the family sailed to New York on the Red Star Line. Whether they stayed in the U.S. or returned to England is a mystery.

Carlisle Kawbawgam is a mystery, too. A Native American of ambiguous ancestry, he may have been a poser (as the British say) or a faker (as the Americans say). Perhaps he fabricated his education at Carlisle and Yale. Perhaps he practiced medicine under false pretenses. We don’t know.

One thing is certain: he dreamed of being an opera star.

Soon after Kawbawgam’s name began to appear in newspapers, a chronicler of Ohio who authored interminable books about the glory days of the frontier, wrote:*

Certainly the Indians did not indulge in any kind of music to

the extent that did other races. They had few songs or refrains, and no musical

instruments worthy of the name. In fact, they were a silent, sullen people, and

did not even indulge in laughter to the extent that other people have. So if we

are to have an Indian singer who is to startle the world with his music, it

only shows what mighty transformation has been wrought in the Indian since he

first met the white man.

*Abraham J. Baughman, Past and Present of Wyandot County, Ohio (1913).

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2022/01/the-mysterious-carlisle-kawbawgam.html

What's truly fascinating about him is a shrewd grasp (quite ahead of his time) of the possibility of using anti-Indian racism to his advantage. He recognized that there was a fascination with the exotic that was a feature of the prejudice, as well as a deep-seated certainty that Native Americans just weren't musical, or even had a sense of humor. And he saw that there was a sort of niche that could be carved out as an Indian who broke out of that box, the exception that proved the rule. It's unclear if he really sang like Caruso, or if he just sang better than the low expectations of white ears, but he seemed to have the last laugh. Or aria, as it were.

ReplyDeleteI wonder if he was a good doctor, and if he used an native medicine.