In New York City toward the end of the nineteenth century, Mary Rankin Cranston lodged in a boarding house on West 56th Street and worked as a librarian at the American Institute of Social Service.

Not long before she started to call herself a “social engineer” and sailed to Europe to make a study of working conditions, she had fled the South and a husband twenty years her senior whom she married when she was a belle of Atlanta.

Born in 1873, daughter of a druggist who called himself a doctor, Mamie Rankin must have had a serious reason for leaving Henry Cranston. Now known as Mary, she “came to New York with a definite and clear idea of what she wanted to do,” according to Success Magazine, which saluted her in 1905.

Cranston had never expected to earn a living but, after training as a librarian, she collaborated with two eminent reformers—Dr. Josiah Strong and Dr. W.H. Tolman—who had just established the Institute. Social betterment and eliminating urban poverty were their crusades.

|

| Dr. Josiah Strong |

Dr. Strong, a Social Gospel adherent whose chauvinistic beliefs about Anglo-Saxonism and Protestantism would be considered unacceptable today, sought solutions to alienation and destitution. Dr. Tolman, who had studied the nascent field of sociology at Johns Hopkins, focused on problems of industrialization and “fresh-air” programs like vacation schools.

It was within this Progressive agenda that Mary Rankin Cranston found a home. A librarian untypical of her time, Cranston created from scratch a “social clearing-house,” she explained to Harper’s Monthly in 1906. All available data and written material related to social improvement and urban issues were gathered in the Institute's library.

She enthusiastically loaned most of the 1,500 volumes, 5,000

pamphlets, and countless articles to social workers, municipal officials, politicians,

business people, clergy, journalists, and students worldwide.

|

| Cranston contributed articles to various publications, including "Homes of the Poor in Large Cities" in the January 1902 issue of Social Service. |

While expanding the

library, Cranston took time to pursue her own research. “The Housing of the

Negro in New York City,” which appeared in Southern Workman, in 1902,

was widely reprinted. She wrote:

If white people have found it a hard

proposition to obtain decent homes in New York, it has been even worse for the

“brother in black” who must here as everywhere else take what he can get

without any choice in the matter. Wherever the Negro has gone—North, East,

South and West—he has found the same prejudice, more or less strongly expressed

in various localities, but always the same thing at the last analysis.

Theoretically some may advocate social equality but usually with the mental

reservation that it shall be at a safe distance from its champions. It is this

prejudice which forces the colored population into almost unhabitable quarters

in our cities, large and small.

|

| Photographs that illustrated Cranston's article, "The Housing of the Negro in New York City." |

A year later, in “The New

Industrialism,” Cranston observed:

The most serious disadvantage to the workingman of the introduction of machinery lies in his danger of becoming a mere machine himself.

Cranston’s lectures and articles began to draw attention from philanthropists like Helen Miller Gould, daughter of the robber baron Jay Gould, who had inherited several of his millions in 1892 and spent much of it on social reform.

Then, suddenly, came change.

Perhaps Cranston seized the idea from the backyard and vacant-lot gardens which had sprung up as antidotes to life in the dirty, unpastoral city. Perhaps she burned out. Either way, by spring of 1910 she was ensconced in an old farm in North Brunswick, N.J.; occupation: poultry farmer.

Cranston spent her savings to purchase the property, which she named “Pendidit” because writing had provided the necessary money. In 1911, Country Life in America featured her as part of its “Cutting Loose from the City” series.

HOW

ONE WOMAN, WITHOUT FAMILY OR MEANS, AND WITHOUT ANY PREVIOUS AGRICULTURAL

EXPERIENCE, HAS LAID THE FOUNDATION FOR AN OLD AGE OF PEACE AND PLENTY, AND AT

THE SAME TIME ADDED A PRESENT ZEST TO LIFE BY GETTING “BACK TO THE LAND”

|

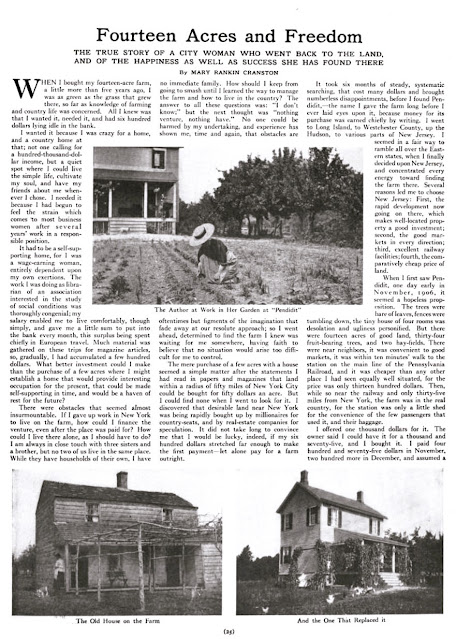

| The first page of Cranston's article, "Fourteen Acres and Freedom" (Suburban Life, 1913) |

Cranston remained a writer and occasionally published articles about farming. And in 1916, the same year that her first husband, Henry Cranston, died in Georgia, she remarried. She and Matthew B. Thomas, a farmer, were together until her death in 1931.

One can’t help asking a few questions about Mary Rankin Cranston Thomas. Of course, many a nineteenth-century Southern belle extricated herself from society and sought education and purpose.

But there’s that twist—walking away from what seemed to be the passion of her life. Especially when she had achieved such success.

Perhaps Cranston’s change

was simple: she answered a second calling.

https://www.throughthehourglass.com/2023/06/the-unexpected-journey-of-mary-rankin.html

1) Is there a Librarian magazine you can submit this to?

ReplyDelete2) So, she left her first husband but there is no evidence of a divorce? What a scandal that must have been back in Atlanta. Perhaps he offered some financial support if she did not ask for a divorce.